100 Ideas for Reducing Crime in Cities—A Blueprint for Action

Creating Portfolios of Human Services and Criminal Justice Initiatives to Improve Public Safety and Justice

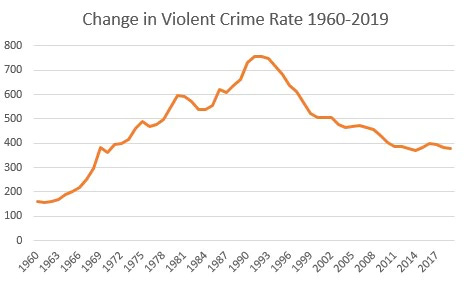

Crime declined rapidly in the 1990s, almost everywhere, and almost all at once. I’ve written a lot about this because there are many lessons from the crime decline that can help to reduce crime and violence today and in the future.

The key lesson from the crime decline of the 1990s is that the most effective crime-fighting tools were not explicitly about fighting crime through the justice system.

The big changes in the 1990s that reduced crime were population-level shifts in culture, markets, and social supports. The society-wide shift from paying for everything in cash to carrying electronic debit cards reduced everyone’s vulnerability. The introduction, availability, and widespread use of mental health medications helped millions to be more resilient. Technological improvements led to better security which safeguarded our homes, are valuables, and ourselves. And the widespread rejection of crack cocaine by potential users eventually withered the volatile drug markets.

As we move forward and apply these lessons, the next phase should be about creating portfolios of programs—violence reduction initiatives that are complementary. There is no single path or program that singularly reduces violence. But there are hundreds of behavioral solutions, market-based solutions, medical solutions, structural solutions, and government nudges. Each, in its own way, reduces risks and promotes resiliency. Some focus on root causes that help everyone, some focus on people and places at particularly high risk, and some focus on interventions for people already in trouble. But all embrace the idea that strengthening people and communities is the surest path to widespread safety.

The idea here is to focus on strategies and programs that allow communities to co-produce public safety. There are complements to—but not substitutes for—law enforcement-led strategies. There are numerous evidence-based law enforcement-focused mechanisms as well and they should be a critical part of any public safety proposal. But, if the arc from Michael Brown to George Floyd taught America anything, it is that we have to move beyond law enforcement working in isolation to find justice.

Three ideas motivate this approach.

No matter how well designed, no single approach is sufficient. Policy is about choices, and giving policymakers a single piece of information, a single piece of the puzzle, with no guidance about how it fits into the larger puzzle—or even how many pieces are in the puzzle—is of little use in making choices.

As is often said, quantity has a quality all its own. If there are 100—or hundreds—of options for improving communities and building resiliency without expanding the justice system, surely there is a portfolio that fits every city.

Each of these options has an evidence base, and there is a link to that evidence. These programs are ready to go, and answer the most important question for local lawmakers—what do we now, today?

The List

In that spirit, here are 100 crime-reducing strategies that strengthen people and communities. In fact, there are more than 300 crime-reducing strategies here since there are often multiple evidence-based strategies within a single initiative. What unites these approaches is that they embrace public health ideas of prevention. Some are universal and reduce risk and improve resiliency for everyone. Some are more targeted, with a specific, high-risk population in mind. All are positive or reduce negatives—none impose sanctions, increase the perception of risk, incapacitate, or punish. And each of these strategies has a substantial body of evidence supporting it.

The Categories

The initiatives are loosely grouped into categories and the category is ranked. Both the categorization and the ranking are subjects for criticism—and that is welcome. The categories provide some useful guidance on how to group evidence-based interventions as a portfolio, and to think about what the elements are for specific strategies targeting specific problems. My contention is that governments would be more successful implementing each category as a portfolio than if they were to implement one, or none, of the initiatives within the category.

The rankings are subjective, as they must be. The rankings consider the strength of the evidence, the cost (and cost-effectiveness) of the category, and the political feasibility of the category. In the end, political feasibility is the most subjective but carries the most weight. There is a brief discussion of the methods after the rankings.

The Rankings

Help Victims of Crime (1-5)

Past victimization of a person or place is the surest predictor of future risk. Among all the ideas on the list, this one has the fewest barriers to implementation, the most potential for positive change, and the least political opposition.

Improve access to victims’ services/victim compensation

Target-harden (cocoon) places that have already been victimized

Reduce trauma for people who have been victimized

Target harden people and places close to those who have been victimized

Fund programs for people experiencing ongoing victimization: domestic violence, teen dating violence, campus sexual assault, and stalking assistance programs

Reduce Demand for Law Enforcement (6-8)

While every item on this list is in one way or another an attempt to reduce demand for law enforcement, these items make demand reduction an explicit goal. Reducing demand for law enforcement reduces the risk of (sometimes deadly) police use of force and other negative externalities of over-policing. It also makes law enforcement more efficient at taking on the tasks that remain.

Reduce demand for police and the number of calls for service (and facilitate co-responders)

Fixing Distressed Spaces (9-13)

There is growing evidence that places poison people—crime does not result from ‘areas’ of the ‘inner city’ being high risk, but rather from a few bad places that are contagious, which can be as scarce as a single house on a block. Concentrated efforts to improve contagious places can build resiliency across neighborhoods.

Beautification (vacant lots remediation and maintenance, community gardens)

Abate nuisance properties (abandoned buildings and other properties)

Abate nuisance businesses (motels, shopping malls)

Policing bad landlords (to reduce blighting and evictions)

Making Crime Attractors Less Appealing (14-18)

Certain places attract and generate crime. But more often than not, careful planning and implementation of best practices in situational crime prevention can reduce the harms they generate.

Enforcing rules for on-premise alcohol outlets

Enforcing rules for off-premise alcohol outlets

Monitoring the school commute

Improve street lighting (short-term and long-term)

Technical, Logistic, and Strategic Supports for Law Enforcement (19-26)

The US military—which local law enforcement is quick to emulate—has sophisticated technical, logistic, and strategic support networks that substantially outnumber the ‘boots on the ground’—a practice the police have been slow to emulate. Bending to the current reality, the International Association of Crime Analysts recommends a ratio of 1 analyst per 30,000 calls for service. But the smaller that ratio, the bigger the improvement in police performance and the greater the reduction in the use of force.

Hire co-responders for 911 calls

Hire civilian intelligence analysts

Hire civilian social media intelligence analysts for policing (and protecting civil liberties)

Expand DNA databases

Collect more DNA evidence (using civilian evidence collectors) from residential burglaries

Hire more staff to provide health and safety supports for police officers

Invest in human resources programs to hire 21st-century police

Improving the Job Market and Job Training (27-31)

The relationship between jobs and crime is far more complex than in the popular imagination—unemployment rates, for example, does not seem related to violence. But jobs matter, and recent efforts to integrate broader skills training into employment for young people have solid evidence of effectiveness.

Encourage learning by doing

Incorporate employment programs for the formerly incarcerated into pre-release planning

Fund transitional jobs for high-risk people

Reduce occupational licensure requirements (hair braiding, etc.)

Facilitate Neighborhood Non-Profits (32-37)

In his excellent book Uneasy Peace, Professor Patrick Sharkey reports on a study that finds that 10 additional nonprofits reduce the violence rate by six percent. This effect can be enhanced with evidence-based nonprofits focusing on specific problems.

Increase the number of community-serving neighborhood-based organizations

Improved access to prescribing physicians and pharmacies for psychotropic medications

Community-focused workforce development

Fund community crisis centers (mental and behavioral health)

Fund juvenile diversion centers

Provide matching funds for neighborhood investments

Make Prison Less Criminogenic (38-40)

The analog to building resiliency in people returning from prison is removing the risk conditions in prison that contribute to, rather than prevent, criminality.

Remove barriers to gaining an education while in prison

Facilitate communication with children, families, and friends

Better Prepare People to Return Home From Prison (41-43)

The rate at which people who have been released from prison are rearrested, reconvicted, and returned to prison is astronomical, suggesting that a corrections model focused exclusively on punishment is wholly counterproductive.

Programs for incarcerated people to prepare them for return

Moment of release programs (license, prescription, housing, etc.)

Post-release programs for people returning from prison

Community-Based Violence Interruption (44-46)

A growing body of evidence finds that credible messengers—individuals with lived experience—can serve as effective intermediaries to prevent retaliatory violence.

… and Cure Violence

Use Technology to Reduce Violence (47-51)

Professor Graham Farrell argues convincingly that increases in security in the 1990s were the only universal explanation for the universal decline in crime. There is much more that can be done without imposing on civil liberties.

Require safety features on consumer products that generate negative externalities

Text message reminders for court appearances in lieu of bail

Create ‘wandering cop’ databases to prohibit the hiring of dangerous officers

Facilitate electronic banking in high-poverty neighborhoods/reduce cash transactions

Prevention Policy (52-57)

Several important prevention policies have been successfully tested but insufficiently implemented by state and local governments. These policy changes are among the highest priority items—but ranked relatively low due to political constraints.

Mandated reimbursement for ACEs testing and social service referrals

Expand and extend HOPE VI

Clinical programs for children with caregivers with OUD/SUD disorders

Use the Bully Pulpit (58-60)

A change in tone and priorities would make cities more appealing in a number of crime-reducing ways.

Encourage immigrants to make your city home

Focus disproportionately on the places that have been left behind

Fix Long-Standing Problems (61-64)

Problems often persist because they have a high cost, a lack of immediacy, and a declining political constituency—but these perpetual problems are often the key risk condition causing crime in a place to persist.

Lead remediation to reduce exposure

Remove indirect caps on evidence-based community non-profits

Design out crime in public transportation

Reform the Criminal Legal System (65-70)

Too many risk conditions are imposed on high-risk people and their removal would serve as an important harm-reducing innovation.

Reduce/remove fees in the criminal legal system

End poverty traps

Pass clean slate laws expunging old convictions

Acknowledge the limits of deterrence on young people’s behavior

Facilitate restorative justice programs

Help those with Substance Use Disorders (71-76)

In the 1990s and 2000s, with trepidation, the justice system began treating substance use disorders as a disease rather than a crime. But, progress has slowed or stopped in the last decade. Many extremely useful ideas were rigorously tested in that period and found to be successful.

Trauma-informed care for high-risk populations (juveniles, veterans, etc.)

Facilitate harm reduction initiatives

Expand evidenced base diversion (24/7 sobriety, drug courts)

Treat withdrawal in jail

Increased use of medically assisted treatment for substance use treatment

Programs for High-Risk Young People and Families (77-82)

A lot of criminology is concerned with bending the criminal trajectory curve—to keep adolescents from accelerating their delinquency or failing to desist as they age—and a huge body of scholarship has contributed to numerous model programs.

Fund programs for youth at high risk of violence and victimization

Fund programs for families at high risk of violence and victimization

Fund universal, school-based prevention (SEL, Life Skills, Good Behavior Game)

Reduce the risks for children in foster care

Education (83-85)

While access to quality schools is critical to creating resiliency, education (and housing) have huge portfolios that are beyond the scope of this essay and thus are low on this list. That said, schools can facilitate crime reduction outside of schools, by incorporating specific initiatives into schools.

Humanize school discipline

Create certification courses for interventionists (community violence, extremism)

Reduce food insecurity through emergency assistance/school breakfast/summer food service

Housing (86-89)

Housing solutions are listed low on this list because 1) they are elements of huge systems with other priorities and 2) they require substantial up-front investments, which should not be a barrier to funding cost-effective initiatives, but is.

Support transitional housing for youth experiencing homelessness

Add trauma-informed elements to permanent supportive housing

Investigate the Familiar Faces program or Modified Assertive Community Treatment for people who frequently cycle through emergency services

Policy and Law (90-93)

There are any number of laws and regulations that could be tweaked that have the potential to meaningfully reduce crime and victimization. This list is a sample of that evidence.

Expand DNA databases

Allow Pigouvian taxes (alcohol, firearms, and other crime polluters)

Make daylight savings time permanent

Reduce Firearms Violence (94-100)

The link between firearms and violence is ironclad and explains much of the difference in rates of violence between the US and peer nations. The category ranks low due because of political interference in implementation.

Close loopholes for background checks for firearms purchase

Better coordination of mental health data for firearms background checks

Expand and enforce extreme risk protection orders

Investigate and prosecute bad gun dealers

Pass child-access protection laws

Raise the age of legal firearms ownership to 21

Repeal Stand Your Ground laws

Methodology

As to the rankings, I used three criteria which I weight more or less equally:

Strength of the evidence

Ease of implementation

Implied cost-benefit ratio

Strength of the Evidence

Behind these rankings lies a huge body of scholarship. Some of these initiatives have been the subject of intense scholarly attention and there are dozens of academic papers exploring the idea. Some have been subject to no research at all but the proposed mechanism has strong theoretical support. using that definition, all of the proposed strategies and initiatives on this list are evidence-based.

Ease of Implementation

In my experience, the biggest obstacle to local implementation of national programs is that people are keenly aware of their own problems and think they are different from everyone else. They suppose, as Tolstoy opens Anna Karina, that “[a]ll happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way." There is little evidence that this is true. Understanding community context is critical, but that does not mean that what works elsewhere won’t work here. A higher ranking was awarded to initiatives that can be easily replicated. A lower ranking was awarded where an initiative has to be carefully tailored to the local context to be effective which creates high implementation costs.

Implied Cost-Benefit Ratio

Policymakers tend to use a simple calculus to evaluate their choices—does the initiative solve a big problem or a small problem? Does it solve all of a big problem or only a small part? Is it risky or fairly certain? In that spirit, strong evidence for low-risk solutions to big problems gets the biggest weight, and so on down the line. But there is a caveat that solutions to problems that reduce the threat of catastrophic events get a bigger weight. Following Naseem Nicholas Talib’s thinking about markets in Black Swan, the biggest threats to a community come from catastrophic events—a community that experiences a mass shooting or a gang war will be traumatized for a generation. Preventing catastrophes should be a top priority.

Political Feasibility

I don’t know a more objective way to evaluate political feasibility than to ask whether a solution has some traction or not. The initiatives to regulate firearms that are proposed here, for instance, are not new. But history suggests that places that have been unwilling to implement these strategies will remain unwilling, and thus they are ranked low.

I look forward to a robust debate.

Thank you for this list. Very helpful!!

Thanks for putting in the hard work towards this pressing issue. Much appreciated