Vivé la Revolution: What would it mean to ‘Win’ the War on Crime?

Creating better measures to evaluate whether the justice system is working

If there is an academic in your life, you know they love the colon. And by colon, I mean the punctuation mark, not the digestive tract. Like, they would be really excited about their new paper, Zen and the Art of Dialectics: Structural Historicism from Parmenides to Hegel and expound on the value of the colon in their title. Interestingly though, like the punctuation mark, the digestive tract is also divided into two parts: the cecum and the rest. The rest is more of a journey than a place and it is almost lyrical: it first ascends, then transverses, and then descends to the finish. Your academic loves their colon for many of the same reasons. But be wary. Colons, I have learned, are the most constrained of the conjunctives. Anyway, the important point here is that the bit before the colon (the punctuation mark) is called the suggestive, and the bit after the colon is called the implicative.

Your academic loves the colon because it allows them to serve two audiences at once. In the cecum or suggestive bit, they can throw a bit of cleverness at the slack-jawed rubes who they imagine will cite them based on the title alone. In the implicative, they can tell you what they really want to talk about.

I say all of this because popular books and movies often do this as well, have a suggestive and an implicative, but in our fever to abbreviate the world around us, we revel in the suggestive and take little note of what comes after the colon, or what I call the post-conjunctive.

Today, I want to write a little about Moneyball and talk a little bit about what it would mean for crime and justice policy and practice. This is well-tread ground, I know. Michael Lewis published Moneyball in 2003 and the term has become shorthand for any data-driven effort to make government more efficient. More on that in a moment. But I want to start with the title of the book, which was not the title of the movie. The title of the movie, Moneyball, is just the suggestive. The full title of the book is Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game.

But before we get to that, I don’t want to assume everyone has now seen the movie or read the book—despite the ubiquity of ‘Moneyball’ in our collective lexicon, the movie didn’t do terribly well at the box office. So, here’s a little plot synopsis. As with any good movie, the place to start is at the end.

After we watch the Oakland A’s go from not so lovable losers to a 20 game winning streak and into the playoffs despite their tiny, shoestring budget but ultimately failing in a David-wounds-Goliath-but-is-finally-mangled-and-crushed story, we get to the final scene—we watch, along with Jonah Hill and Brad Pitt, a video of a minor leaguer in a pivotal at-bat, and the obvious back-story here is that the batter is a hefty guy who is too hefty to be successful, but despite that he smacks a pitch deep into the night and he runs fearfully and ponderously to first and falls spectacularly rounding the base, but then he is helped to his feet by the opposition and told he’s hit a home run, and Jonah Hill looks deeply into Brad Pitt’s eyes and says, “it’s a metaphor” and Brad Pitt gets misty and says, “you’re a good egg” and everybody has a good cry and roll credits.

Thanks in no small part to Brad Pitts’ misty eyes, in addition to Moneyball for Baseball we now have Moneyball for Government and Moneyball for International Relations and Moneyball for Etsy and Moneyball for everything else. But lost in all of this is the real point of the Michael Lewis book, which is the implicative, “The Art of Winning an Unfair Game.”

There is no more of an unfair game than the American criminal justice system, and that is what I really want to talk about. What it means to ‘win’.

***

In our zeal to implement Moneyball everywhere, we seem to have forgotten just what the idea of Moneyball was all about. Today, the idea of Moneyball in the real world seems to be exclusively about the data: identifying data, accumulating data, and having data. The idea seems to be that if we collect and have enough data, better policy will result. Data is certainly a necessary condition for better policy. But it’s hardly sufficient.

What gets lost is the initial premise of Moneyball from its progenitor Bill James, a former security guard at Stokely-Van Camp's pork and beans cannery. The Jamesian worldview was extremely simple. The goal of baseball is to win games. The way games are won is that more runs are scored than are given up. Thus, teams should seek to score as many runs as possible. The only way a run is scored is if a runner gets on base. Therefore, above all else, baseball teams should prize batters who get on base.

And… that’s it. That’s the theory. Vivé la Revolution!!

If all of this preamble has itself been a metaphor, which seems plausible, then the point is to ask, what does it mean to ‘win’ in crime policy? If policy is about winning an unfair game, the place to start is to figure out how you would know if you won. And that is a lot harder than it sounds.

I want to first describe the four most prominent measures of our collective success in the fight against crime and why a different measure is needed. And I want to propose a new measure, one that gets very little attention but has a number of attractive qualities.

Counting the Number of Crimes

Ten years ago, or maybe even five years ago, the answer to this question ‘how do we know if we are winning the fight with crime’ would have been: winning the war on crime, violence, and victimization means reducing the number of crimes. Today though, that answer seems woefully inadequate. It is inadequate because too much of historical crime policy has been about reducing crime and violence by reducing the number of white victims but not the number of black victims and the obvious inequity of that approach has finally become obvious. The other problem with the ‘count the crimes’ approach is that it treats victimization as an undifferentiated commodity where each event counts the same. At the grossest level, this is obviously wrong, as it fails at the very first point of differentiation—‘crime’ and ‘violence’ are not the same. This is just the tip of the iceberg where the iceberg is all of the reasons just counting crimes as a measure of success is simple, intuitive, and wrong. Counts of crime have proven to be an extremely ineffective and often counterproductive measure of the effectiveness of justice policy and it’s time to move on.

Measures of Harms from Crime and Violence

One common solution to the commoditization of crime problem is to differentiate victimization experiences by putting a value on the harms from crime. What this does is move from a focus on counting crimes to a focus on victims. In 1999, David Anderson estimated that the total harm from crime in the US exceeded $1 trillion—in November 2021, Anderson published an update and estimated that the harms from criminal victimization had more than tripled in the last twenty years even though overall crime is about the same. These estimates are not out of line with work by Cohen and Piquero and Ludwig. I also have written a lot about harm to victims, but I am keenly aware of the limits of the method and what needs to be done to fix it. Currently, our confidence intervals are so wide around estimates of harms to victims that it would be almost impossible to distinguish a real reduction from noise or chance. Still, we should continue pushing this rock up the hill and improve our estimates of the harms from victimization. But this measurement tool is not yet ready to define the success or failure of crime policy.

Measures of System Equity

There is no doubt that the criminal justice system is astonishingly inequitable. It is far harder to find some segment of criminal case processing that is approximately equitable than to find one that is not. Radley Balko at the Washington Post has published an exhaustive list of studies showing racial disparities in the system—Mike Shor has an even longer list on Twitter. Still, by itself, measures of equity are incomplete. If the goal of policy is to make the system more equitable, that can be done without reducing crime and violence: there can be equity at high levels of crime and violence as well as at low levels of crime and violence. Certainly, a case can be made that making the system more equitable will, by itself, reduce crime, violence, and victimization. But there are too few examples of real places that have chosen to focus on equity, so we simply do not know yet how big the impact of a more equitable system on victimization would be. We need measures of both equity and victimization.

Measures of System Fairness

A somewhat related idea of what it means to ‘win’ the fight against crime would be to make the justice system fairer and to measure those changes. I know some will disagree, but I do think it is reasonable to separate equity—which is about treating people of color the same as everyone—and fairness, which is about changing the rules of the system so that the process gives people more humanity. For example, fairness would include reforms like not ramming cases through criminal case processing with plea bargains in virtually every criminal case, where the criminal defendant has essentially no voice in their defense. Fairness as a measure, however, examines what happens after people have contact with the justice system rather than reducing the number of people who have any contact with the system at all. Again, fairness is a necessary but insufficient condition to understand the whole trajectory of crime, violence, and victimization.

Winning the War on Crime by Reducing Police-Public Contacts

The discussion about measuring fairness opens up a door to a very different measure of ‘winning’ in the fight on crime, violence, and victimization. One that has not been entertained, to date, as far as I can tell.

What if the goal of the justice system was simply to have fewer people have contact with it? What if ‘winning’ meant gradually putting the criminal justice system out of business? Prosecutors, police, and judges say this all the time, that their goal is put themselves out of business. What if we actually applied that standard?

This seems like the clearest analog to runs scored in baseball in our Moneyball for Crime. The policy that leads to the fewest number of justice system contacts with the public wins. Let’s pull on this thread and see if it unravels.

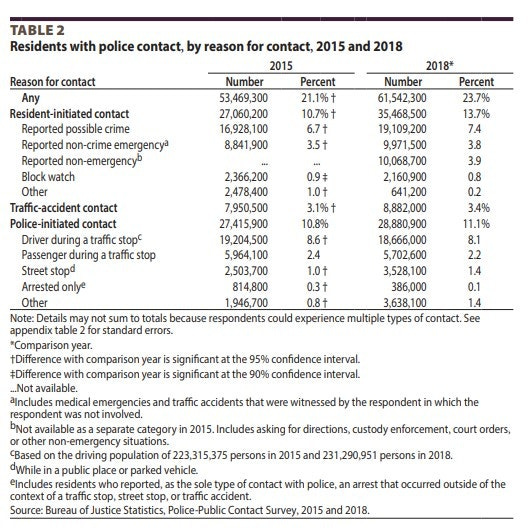

First, some data (of course). Every year since 1973, the US Department of Justice has fielded the National Crime Victimization Survey (the NCVS). Twice in the last ten years, in 2015 and 2018, the Justice Department has commissioned an eponymous supplement called the Police-Public Contact Survey (the PPCS). Both years of survey data come to roughly the same conclusion.

In 2018, about one-quarter of US residents over the age of 16 (61.5 million) reported contact with the police. I’ve argued before that a lot of policymaking comes down to deciding whether a statistic is a big number or a small number. Sixty-one and half million police contacts in a single year. There’s no way to downplay it, that’s just a huge number.

Now, a fair question is, what should that number be? I don’t think there is anyone, anywhere, even the most avid fan of law and order, who would argue that number is too small and there should be more contact between the public and the police. Maybe it is a failure of imagination, but I can’t conjure an argument for more. So, 61.5 million contacts per year is either just right, or, the number should be smaller.

But how much smaller? A little smaller or a lot smaller? If the answer is: a little smaller, then it is not much of a measure. But if the answer is: a lot smaller, and, if there are costs to those contacts, then it could be a good candidate as a measure.

I don’t think the statement that there are costs to policing is particularly controversial. There is a huge literature to cite here, but I will just mention the costs of coercion and let it go at that [italics added].

Coercion is not the goal of policing. It is its tool. We allow police to make arrests, use force, and search and seize property to enable the prosecution of crimes and the protection of public safety and order, not as ends in themselves. There are myriad benefits that come from lawful and effective law enforcement, but the coercive tools of policing are also socially costly. They intrude upon individuals, their families, and often whole communities, causing injury, suffering, and fear. Those harms are sometimes worth suffering, at least to society as a whole, because they are part of the price we pay for the security and order we seek. Moreover, they are also often justifiable against individuals who have committed or are suspected of committing crimes. Still, coercion is costly, and policing policy should minimize those costs. Like other public services, good policing is efficient as well as effective.

Having established that policing is costly, it is fair to ask, how many of the 61.5 million police contacts each year are interactions for which only the police are qualified? That is, how many of these are things only the police could do, and, how many of these contacts involve an interaction something or someone else could do? To answer that question, just as a thought experiment, let’s imagine that the someone else is either ‘technology’, or, a perfectly average American—38 years old, as likely to be a man as a woman, maybe 5’8” and 160 lbs, wearing a fluorescent vest and wielding a walkie talkie.

So, how many of these contacts must include an armed, uniformed police officer? Here’s the table from the PPCS that describes the types of police-public contact.

Just taking a quick look at the 2018 data, the answer seems to be: not as many as you would think. Out of 61.5 million contacts, 20 million are for a non-crime emergency or a non-emergency. Another almost nine million are for traffic accidents. Now, there are certainly instances where a uniformed police officer may be needed, but overwhelmingly, someone else—our average American with the fluorescent vest and a walkie-talkie—and without the power of arrest—would have been an excellent substitute. And without the costs of coercion.

Instead of going through this table line by line, I would encourage you to think about each of these categories and ask yourself: could some meaningful proportion of these events be handled by technology (traffic cameras and license plate readers, for example) or our walkie-talkie wielding citizen? It seems pretty obvious to me that there could be a huge reduction in police-public contacts with little risk to public safety.

Now, for my friends for the law and order side of the aisle, something for you. I absolutely recognize that there is a floor to the number of contacts. Estimates of the routine activities of police estimated from calls for service data suggest less than 5 percent of all calls for service are for violence. However, this does mean that something like 3 to 4 million calls annually were in response to violence or the threat of violence. There are also about 10 million people booked into jail annually (however, one out of three felony arrestees are not convicted and about half of those arrested for less serious crimes are not charged). And the presence of police, of course, deters violence and keeps people from going to jail in some situations. So maybe the number is 15 million: 15 million or so police-public contacts that are simply unavoidable. And 45 million that are avoidable. And a strong caveat on the unavoidable contacts—there is lots of good research on programs and policies that could reduce that number through prevention. And, I would point out, this shift would free up a tremendous amount of policing resources to focus on deterring and solving violent crimes, resources that are badly needed.

A Thought Experiment

I would note that it is fair to be concerned that my approach of reducing police-public contacts could be achieved in really inequitable and unfair ways. But I don’t think it would. If you work through this thought experiment you will be convinced, I think, that policies that promote equity and fairness are the best means to reduce the number of police-public contacts. I think you will also be convinced that there are all kinds of positive externalities that result from this approach.

Suppose that someone reads this Substack and convinces the Biden administration to set a national target of cutting the number of police-public contacts in half by 2030. Suppose that mayors and county executives around the country also embrace this idea and we are all committed to reducing the number of police-public contacts to 30 million a year.

How will they achieve this goal?

Interestingly, no one’s first thought will be to hire more police. Sure more police could cut crime at the margin and might ultimately lead to the need for fewer police, but it will almost certainly increase the number of contacts by the same margin, if not more.

And no one’s first thought will be to build more prisons. Research shows that if you build it they will come—and to fill those beds, lots of additional arrests will have to be made. And even more police contacts will have to be made to generate those arrests.

So, just by thinking through our Moneyball for Crime goals, just by looking for an analog to runs in baseball, we have completely upended the way we think about criminal justice. And take our two most foundational—and inequitable—ideas off the table.

What’s left are a lot of reasonable strategies to automate traffic enforcement and to add civilians to our public safety corps to respond to the tens of millions of non-emergency requests for help.

Vivé la Revolution!!

After the revolution, what's the plan?

My next assignment for you is to develop a list of citizen / justice systems contacts in which the citizens enjoy some agency and count those. Score jury trials as a positive good instead of an expensive nuisance; participation in sentinel event reviews as a contribution, restorative justice and other collaborative and endeavors in which citizens (and residents) exercise some power.....