Why do people buy guns? There are oceans of opinions about this, but somehow the simplest answer gets little attention: someone is willing to sell a gun to a person at a price they are willing to pay. And why have gun sales gone up so much in the last 20 years, and boy have they ever? Maybe, it’s simply that gun marketers have finely tuned their marketing pitch. They introduced a new product, the AR-15, in time for the end of the Assault Weapons ban in the mid-2000s and branded it ‘America’s Sporting Rifle’. Through it and other market homeruns, they were able not only to bring new people into their market but also to achieve the Holy Grail in the world of sales: getting someone to buy something they already have.

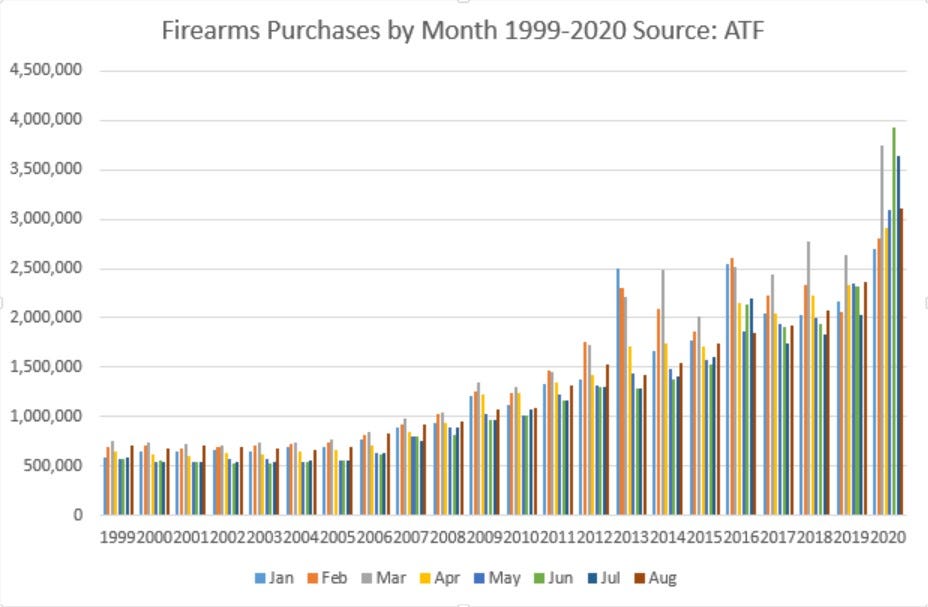

Looking at gun sales as reported to the ATF from 1999 to August 2020, it’s clear there are two periods of gun sales: the before the end of the Assault Weapons Ban (pre-2005) when sales were flat, and the after the ban period when sales rose steadily. I cut these data to just show January through August because sales around Christmas are quite variable for reasons that probably disguise the long-term trend. And this picture suggests that this consumer product became quite popular on its own. Yes, there are outside shocks, Obama’s inaugurations in 2009 and 2013 and Hillary Clinton’s candidacy in 2016, but the trend has been notably stable. Until this year, of course, when sales have skyrocketed due to COVID-19.

But overall, this looks like a market that is growing organically, steadily and rapidly. And that is really important information if you think a better regulated gun market would make us all safer.

To understand why the gun market is growing rapidly, you have to accept on some level that guns are just another consumer product. And that they are a commodity, like cars or TVs. You may prefer one brand over another, but they are basically undifferentiated products. And what makes you prefer one brand over another?

Marketing.

So, what is the magic marketing formula that is selling guns like hot cakes in America? The place to go to figure that out is the NRA. The genius of the NRA is that it is not just a trade association, but the lead marketing agency for the entire industry. It is a way to create monopoly advantages on one key cost driver—advertising—without running afoul of anti-trust laws. And the NRA has clearly tapped into something deep in the American psyche.

Marketers know that to sell a product you have to sell an emotion. Tobacco companies figured this out early on and the emotion they sold was the yearning to be cool. When I was a teenager, the Marlboro man was everywhere. Every teen and twentysomething I knew who smoked—which was some of them in the daylight and all of them at parties—yearned for the cool factor. None of them wanted to be a cowboy, but there were a million different images of cool with a cigarette, enough to fit everybody’s daydreams. Movie stars, pop stars, rock stars, serious intellectuals, surfer bums, your cool cousin, maybe even your mom and dad. Everyone has some icon of cool, and it was easy to find that idol smoking a butt.

So what emotion do gun manufacturers sell? I think the way to understand this is to focus on the outcomes of the public policy’s the NRA promotes. What their sponsored legislation actually does once implemented is the best indicator of what they are selling. Probably the most successful venture in the history of the NRA was their promotion of Stand Your Ground (SYG) laws.

The principle behind SYG is that ordinary people should be able to use deadly force to protect themselves when threatened, without a duty to retreat. Stand Your Ground laws expand gun rights by extending the legitimate use of a gun beyond the Castle (your home) into the public sphere (most anywhere you have a legal right to be). Depending on how you count, around 24 states passed these laws in a rush between 2005 and 2011. It is instructive that both advocates and opponents call Stand Your Ground ‘Make My Day’ laws and see that moniker as supporting their position.

The thing about Stand Your Ground laws is that they solve no problem. This is important. Logically, the reason to have this law is that there have been terrible miscarriages of justice where people have used deadly force in public spaces and subsequently been wrongfully convicted. To right these wrongs, here comes SYG laws to give people the same legal protections to shoot people in the public square that they have in their homes.

Only, there haven’t been any miscarriages of justice of this sort. At least there weren’t stories of injustice trotted out for state legislators to ponder. None. Stand Your Ground is a classic solution in search of a problem. There is no evidence of even a single wrongful conviction where, if there had only had a SYG law justice would have prevailed. So what on earth is going on here?

When people tell you who they are, believe them. Here’s what the data tell us about who SYG is. SYG dramatically increases the likelihood that white people who shoot black people will not be prosecuted. “The starkest contrast is between homicides of blacks committed by whites, of which 11.4 percent are justified, and homicides of whites committed by blacks, of which 1.2 percent are justified.” You can read more here. The racial impact of SYG is crystal clear.

What is less well understood is how it impacts women. I did some analysis for a wonderful piece Liz Flock wrote for the New Yorker on how far women can go to protect themselves. I used SYG to data to understand whether women can use the law to protect themselves in cases of domestic abuse. While the law offers a little smidge of a bit of protection for victims of abuse, it uncovers something else really notable. And it is this. Looking at cases where women kill a man, the likelihood a homicide is found to be justified is:

1.33% in both SYG states and non-SYG states for non-stranger homicides; but

9.55% in SYG states for stranger homicides; and

7.45% in non-SYG states for stranger homicides.

Where Stand Your Ground really helps is offering protection for people who shoot to kill outside their homes. And not just killing anybody outside your home, but it particularly protects people who kill strangers. Remember, there are no cases of wrongful conviction that SYG corrects, these are no injustices that are being salvaged. This law just extends your right to shoot a stranger who scares you.

When you look at the race data on SYG with this new perspective, it becomes much clearer. There is clearly a stranger story there too. When black people kill black people, and, when white people kill white people, they are sometimes strangers, but more often they are people who are at least acquainted with each other. SYG helps them a little, like it helps women in abusive relationships a little. But the people it really helps are white people who kill black people, and they are generally strangers. And the literature is clear that white people incongruously view black people as threats.

So, this appears to answer the question, what is the NRA marketing? Clearly, the NRA is marketing fear. And not just any old fear, not fear of the crazy guy down the street, not fear of the jack-booted government thugs, but fear of strangers. Fear sells, and stranger fear sells best of all. The post 9/11 story is one of a fearful America, where we see something (strange) and say something.

Perhaps that doesn’t sound that insightful, but the narrative of why people who didn’t have guns now buy guns, and why people who had guns now buy many, many new guns tends to omit this obvious reflection. Buying guns is not about military cosplay, or fear of the government, or expressing 2nd amendments. It’s about fear. And that fear is actively and meticulously marketed.

There is no, ahem, silver bullet to solve this problem. But there is an idea. The opposite of fear is not safety—we’ve seen tremendous declines in violent crime and that has not affected fear at all (I wrote about this a little). The opposite of fear is not really even bravery. People who face combat with valor often later report having been terrified in the moment. And really, there is not much that can be done to instill bravery at the population-level.

No, the opposite of fear is trust. And there is a lot that can be done to build trust in our institutions and in each other. It’s a fertile field to explore and we should start taking it more seriously. We shouldn’t wait until someone puts a gun to our head.

Making Lemonade out of Lies

Speaking of the public square, I find myself derailed, yet again, by the mayhem. The idea of this newsletter is to chew on ideas that can sharpen public debate by weaving together insights from a variety of academically-minded sources. The deep irony is that during an election, when you might imagine (and perhaps our Constitutional framers imagined) pointed debates about policy disagreements would dominate the narrative. Instead, policy is submerged into the abyss. There is little if any thoughtful discourse as we creep toward Election Day and our three-dimensional world collapses into a two-dimensional bas-relief.

What is there to say about policy when anonymous commentators ceaselessly hurl invective at political foes and damn them as traitors and allow them no standing in the political marketplace of ideas and ideals?

First, it is important to note that all is not lost. Shrewd readers will recognize among the invective hurlers many of the wily techniques employed by the same founders we imagine to be rolling about in their graves, their eternal rest disturbed by our preference for nihilism over democracy. Ben Franklin was the master of the anonymous letter to the editor and gleefully slandered and libeled his opponents. In his pre-founder days, Franklin’s inventions included many of the tactics Putin’s comrades use to spew policy waste from the foothills of the Ural Mountains. The Internet Research Agency is just a modern take within the long history of trolling. It’s fair to edit the historical tomes of western civilization and substitute ‘Facebook screed’ for ‘pamphlet’ and be more or less correct. Thomas Paine and Ben Franklin were just much better writers.

So what to make of the pre-election silly season? If you are a serious adherent to the idea that history is long but it bends toward justice, than you can take comfort that time will heel the wounds and wound the heels. And it usually does. It is worth noting that the reactionary takes of today, the political nihilism today, is in direct response to advances in justice over the last generation. Whether or not you are convinced that America has gone far enough in extending human rights to all of its citizens it must be accepted that these rights have been dramatically expanded over the last generation or two. The world confronted by my Gen Z children is remarkably different than the one their Gen X father remembers from his childhood. We are bending toward justice.

That should brace the policy-minded among us. I happily admit I no longer contribute to politics and electioneering. I served my time in that particular salt mine 30 years ago. Like all combat, it is mainly a young person’s game. I do, however, think that the calcified ideas that are the trusty rifles of political warfare and that seem to take hold of our baser instincts can be quietly shaped by better ideas.

As Robert Pirsig pointed out 50 years ago, we all know quality when we see it.

A note on self-published scholarship

This, is an essay.

In the pantheon of trite but truisms, ‘anecdotes are not data’ really stands the test of time. If you tell me a theory and then give me an example to give it color and depth, I feel more informed. If instead you present me the same story and then weave a theory from it, I feel snookered. There are 8 million stories in the naked city, and there are X number of stories in your data with X observations. Rich and meaningful to be sure, but never conclusive, because the richness of life and storytelling and data analysis lies in the shape of the function and its distribution, and all the points along the way and their density and slope. If you tell me about a data point in the tail of your distribution I will be fully engaged. If you tell me about one data point without telling me where it is in your distribution or if it is in the tail or at the mean or somewhere else, it is just an advertisement.

I would like to add a new truism to the narrative, which is, ‘unpublished scholarship is an essay’. A professor will puff at the notion that their thinking is undifferentiated from my son’s high school essay, but there it is and you should not shrink from it. That an essay is published on SSRN rather than Medium or Substack, does not give it any additional weight. There are beautiful, moving, insightful, intellectually devastating essays on Medium and there are brilliant essays on SSRN that never crack the peer review granite. Calling something an essay does not diminish it—this particular screed, for instance, is an essay and I feel undiminished in saying so—but it does clarify its standing in the marketplace of ideas.

So why bring this up? In the rush to bloviate about police reform, SSRN articles masquerading as scholarship are proliferating like bunnies in a foxless prairie. Gathering like post-recess clumps of mud in the elementary school foyer. They are spinning up like a derecho in the plains. In simile-land, I prefer the derecho. Derechos are wild and destructive and almost impossible to predict. They seem to develop not where you would expect, where there is a weakness and where there is low pressure, but rather at the junction of systems of fair weather, along the boundaries of high pressure systems. Following this metaphor along, it is the sin of generalizing expertise that is being committed on SSRN. Because I know an enormous amount about this one thing, I feel free to pontificate not just about this adjacent thing but also about this whole other thing of which the thing I know is just a small part. I gussy it up with the usual citations and format it in LaTeX or Computer Modern and it passes for the real thing.

This is a sin of commission, not a sin of omission. Publishing on SSRN without some disclaimer obfuscates, and on purpose. In the rush to get ideas into the narrative, these derechos can wreak havoc because those outside of academia should not be asked to sleuth out whether this is a real paper on its way through the peer review process or an opinion piece in disguise. This is a not so subtle slight of hand that seeks to promote work on a topic that maybe they don’t know that much about using methods that might be found to be unscientific as a finished product. The solution is simple. Add a disclaimer to your SSRN article. Say, “This work has been submitted for peer review. But for now,”

This, is an essay.

RBG

I was deeply saddened by the passing of Ruth Bader Ginsburg. I’ve never thought of someone’s death as disheartening before. Death is traumatic, and the lesson of death and love is that it changes your course and your path, often permanently. But RBG’s death was truly disheartening to me because it was the loss of hope and competence and grace, surely a combination that comes along too seldom, and I don’t see those qualities celebrated as they should be today. And I do want to quibble with the popular elegy that above all else RBG was a hero to girls and women and a guiding pillar for their dreams and ambition. She was a hero to me too.

Data

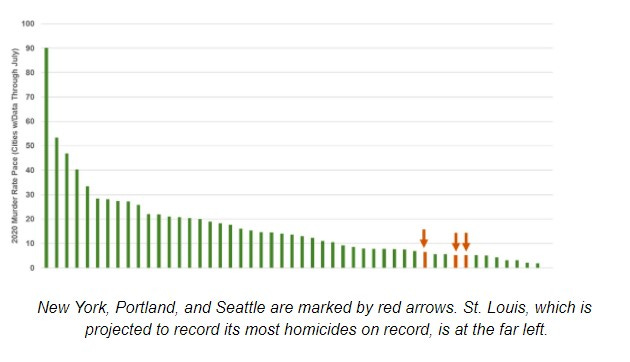

@TeamTrace and @JeffAsher make the point that the three Department of Justice designated ‘anarchist cities’ are actually among the least dangerous of America’s largest 50 cities.

Musical Interlude

Tiny Dancer.