Why This Time is Different

The Utter Failure of the Uvalde PD Changes the Narrative About Gun Safety

The idea of this letter is simple enough—this time it is different for restrictions on guns.

I have been in the business of researching crime and violence for 25 years. Sometime after Sandy Hook, I read a report describing what happened in those two classrooms, in the first classroom, and I carry it with me. If you set aside those who fought for and against gun safety in the days after the tragedy, I suppose Sandy Hook was just too painful to process for the rest of us. Too sad to fight and relive. And so nothing happened.

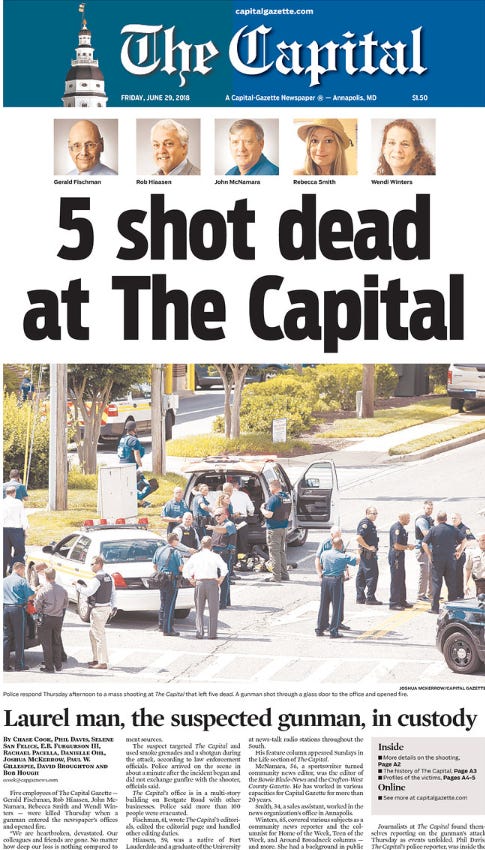

And there was horror after horror in Parkland and Las Vegas and Orlando and Charleston and more. As a young guy, I worked a few months in a cramped little newsroom with the most interesting people while I tried to figure out if I had what it takes to be a reporter. In 2018, five people were killed in the newsroom of the Capital Gazette just a few miles up the road. And they still put out the paper the next day. But nothing happened then either.

The context of this moment is the horror of Robb Elementary. It's immoral to rank atrocities, to even conceive of them in that way, but it is just different when the victims are little. They have a special vulnerability and we have a collective responsibility for their well-being.

An attack on children with semi-automatic weapons is horrifying on its own, but the real accelerant here, the reason why this time is different, is that the police failed utterly in Uvalde. Uvalde PD did not rush in and save the day. They did not rush in at all. They were cowards when heroes were needed.

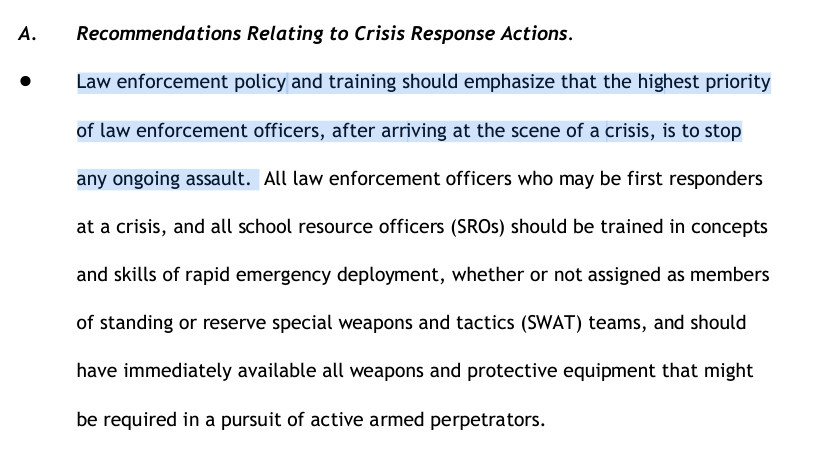

Since Columbine, we have known that the way to save children in school massacres is to fight your way in, without reservation. We have known that whatever happened before the police arrived, once they got there, they would end it. The Secret Service laid out this first responder plan in 2002, and the Department of Justice and the Department of Education have poured resources into training ever since.

Up until now though, this training has not been fully tested. At Sandy Hook, the gunman apparently took his own life when the first officers entered the building. In Parkland, the armed school resource officer hid throughout the incident and at least eight deputies from the Broward County Sheriff’s office take the time not only to take off some gear to put on their bulletproof vests but took the time to stow that gear while shots rang out from the school. By the time officers entered the building 11 minutes after the first shots are fired, the shooter has long since run away. The shooting happened so quickly, however—six minutes—that it is not clear how much of an impact the weak police response caused.

So, the narrative that the police will respond vigorously and heroically when school kids are threatened has remained relatively untested. Faith in the police is our collective bulwark against school massacres.

But not anymore. What was lost in Uvalde was that childlike innocence, where hope becomes fact, that regardless of what happens in our policy and political fights, wherever you land on backing the blue or defunding the police, when the bullets fly and threaten our kids, by God, the police are going to bust in there and get them, their safety be damned.

Except they didn’t.

Except they didn’t. There doesn’t seem anything terribly unusual about the Uvalde PD. It’s not especially small, poorly trained, or lacking key resources. There have been no major scandals that rocked the department, unlike so many others. And that’s the thing that makes this different, that the Uvalde PD is not different. The Uvalde police did not go in and get those kids out. And since there is nothing unusual about the Uvalde cops, nothing that makes them different from your hometown cops, that means your cops won’t go in and get your kids out either because your cops are just like the Uvalde cops.

And that’s the thing that makes all the difference.

Private Costs and Public Costs

Let me try and explain how this calculus works more formally. It is well established that when people are asked about the policy preferences around gun safety, they overwhelmingly support restrictions on guns. I helped put together some questions for a NORC poll that was conducted on March 3–7, 2022, during a monthly Omnibus survey. It included 1,106 interviews with a nationally representative sample (margin of error +/- 3.85 percent) of adult Americans age 18+ using the national probability-based AmeriSpeak® Panel.

86% of Americans favor “Preventing people with mental illnesses from purchasing guns”

86% of Americans favor “Making private gun sales and sales at gun shows subject to background checks”

71% of Americans favor “Creating a federal government database to track all gun sales”

In a highly partisan environment, these percentages are gravity-defying—they amount to as close to a consensus as we are likely to come in modern America on any issue. So, why aren’t any of these preferences being voted into law?

The answer is that when people are asked to rank-order their preferences—when they are asked to prioritize what should be done first—gun law changes fall way down the list, below things like inflation and health care. And that makes a lot of sense if you separate people’s policy priorities into their public preferences and their private preferences.

I think of public preferences as almost existential. These are things I am for because they are good public policy or they align with my values. These are things I think of as being in the public interest. These are things that improve the common good. But, alas, the Tragedy of the Commons works both ways.

In the classic Tragedy of the Commons allegory, a town square is open to grazing by all the townsfolk’s cattle. Because the land is commonly held and no one is charged for its use, it will inevitably be overused. It is quite reasonable, in fact, for the townsfolk to stop grazing on their own land—which creates a personal expense—and move the cattle to the public space. In the this-is-literally-why-we-can’t-have-nice-things finale, the public space is ruined.

But the lesson that often gets lost a little in our concern about how public spaces are treated is that given a choice, private interests trump public interests. And the same is true for policy rankings. What I rank high on my policy priorities are those things that have high private costs, not high public costs. This is why health care and inflation rank highly—they are intensely personal costs. And why background checks lag.

We get thrown off by the fact that virtually everyone agrees on this issue—we are a bit deluded by the near-consensus (86 percent favor background checks). But just because everyone agrees and shares an opinion does not mean they all feel strongly about it.

In sum, for those favoring gun law restrictions, their preferences are predominantly public interest preferences but not private interest preferences.

Now, let’s flip the script and look at those who favor loosening gun laws.

24% of Americans favor “Allowing people to carry concealed guns without a permit”

For these people, the policy preference is both a public cost and a private cost. The public cost is that they see gun-carrying as in the public’s interest. It is also an intensely personal cost because they want to carry their own gun without a permit, which is materially different than wanting someone else to get a background check.

Why this Time is Different Part II

If you put the two parts of this essay together, it’s easy to see how Uvalde may shift the narrative by making what had been mainly public preferences private. If I worry about my kids being shot at school, and I worry that the frequency and intensity of these events are increasing, I start to privatize my concerns.

If I begin to believe that there is no recourse—that the police are not coming to save my kids. That when my kids are threatened, the police will just stand outside my kid's school for 78 minutes while my children are terrorized by a gunman. Then it is personal. Deeply personal. Unavoidably personal, even if I do not care for politics and am part of the largest block of voters there is—the nonvoter.

Coda

There is no reason to believe that absent some pretty fundamental shift in gun laws, the threat of mass shootings will dissipate. There are more mass shootings than ten years ago. And while the number of mass shootings increases, the number of weapons available to be used in a mass shooting also continues to increase—sometime this summer, the 50 millionth gun will be sold in America just since January 1, 2020. There is simply no reason to believe the number of mass shootings is going to decline. And every minute the Uvalde police spent milling around outside Robb Elementary reduced the deterrent effect of the police.

There’s just no reason to think any of this is going to stop on its own or even get better. Put all of this together and all you see is momentum inexorably building for gun safety measures. And it is not just about doing something to go to the voters and say, look, we did something. Until those gun safety measures are of sufficient scale to actually improve public safety—to actually reduce the number of mass shootings—the pressure will only continue to build.