Here, I want to make a forecast for crime and violence in the US. Getting there responsibly is a bit of a journey. Let me first defend the idea that crime has declined because there is skepticism about this idea from many corners and not just for partisan reasons. Then, let me make a case for some specific causes of the crime decline. If you are going to make a forecast, you first must be clear-eyed about why the world today is the way it is. And then let me write a little about what is—and what is not—influencing crime trends right now and what that means for the future. It’s a mostly sunny journey, let’s get to it.

The Crime Decline Consensus

The results are in: violence has declined. Over the last few months, five studies have measured crime in 2024 as compared to crime in 2023 and all the conclusions are the same, even though the data sources are quite different.

The evidence is overwhelming enough at this point that the decline should be taken as an accepted fact. The debate continues, but only because there are built-in incentives for advocates claiming an unyielding spiral of decay. Popular conspiracies include the idea that the almost 19,000 police agencies in the US have conspired in some fearsome way to cook the books to hide the grim reality of ever-increasing crime. Or, that the police no longer respond to desperate calls for service because <waves hands> and thus the people have become so disheartened they no longer call for help, suffering silently, even when there is murder. Or, that while some crime might be down, antihistamines are now sequestered behind a plastic guard at the pharmacy, so we must immediately abandon the cities. And there was a flash mob of robbers at a Louis Vitton in Los Angeles a couple of years ago. End times, for sure.

But all of this is beside the point. Because the point is that crime, particularly violence, is declining, it would be clever to figure out why.

Why is Violence Declining?

I’ve shown this graph a couple of times before, but it’s worth highlighting again for a couple of reasons. First, the trend in violent crime is not just down, it is accelerating. Compared to the first half of 2023, homicide through the first half of 2024 looks to be declining faster than it did comparing 2023 to 2022 (which was itself a historic decline). See my paper here with Kiegan Rice for a full explanation.

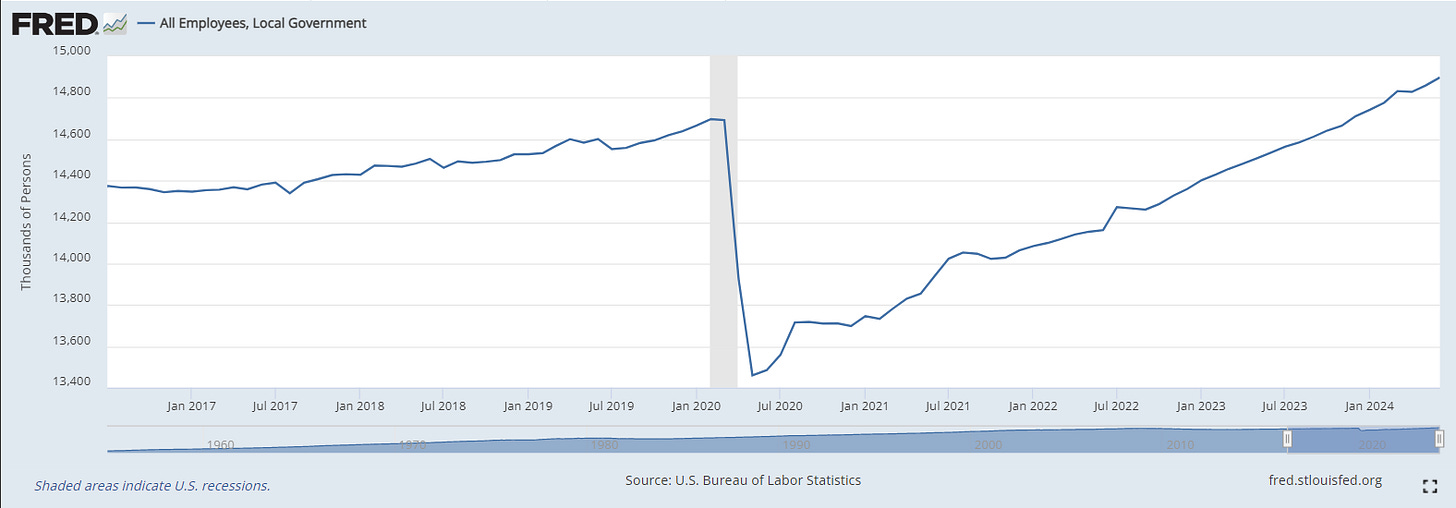

I’ve also made the case before that the trend in local government employment is an important indicator of why crime spiked in 2020 and has plummeted since. I won’t repeat those arguments, but there are compelling empirical and theoretical reasons to believe that the ebb and flow of the number of people working in jobs that directly connect with young people at high risk of violence and victimization is predictive of crime trends.

Between March 2020 and May 2020, more than 1.25 million local government jobs (teachers, counselors, social workers, police, etc.) were lost at the same time violence spike. Once local government employment levels began a steady increase in early 2023, the trend reverse and crime levels crashed. It’s a correlation, but compelling.

Second, it is interesting to note that when comparing the before-the-pandemic period with the after-pandemic period, the rate of local government job growth was far more rapid in the post-pandemic period. The graph below is a pre-post comparison of local government employment levels, comparing 42 months before the pandemic with 42 months after.

The pre-period begins July 1, 2016, roughly three and a half years before the beginning of 2020 and the pandemic period. In that 42-month period, local government employment generally increased, from 14.374 million to 14.666 million new jobs, an increase of 292,000 jobs. But the rate of increase was small, a little less than 7,000 jobs added per month.

The post period begins in December 2020 and during this period local government jobs increased from 13.698 million to 14.898 million. That’s an increase of 1.2 million jobs in 42 months. An average of 28,500 jobs were added in each of the 42 months, about four times faster than in the pre-pandemic period.

Even more interesting, beginning in September 2022, which seems to be around the tipping point for violence, the growth in local jobs became extremely consistent. Over the next 22 months, about 29,000 local jobs were added each month, with little variation. So that would create two important elements. One is that local government jobs—teachers, counselors, hospital workers, coaches, judges, police, and grants administrators—were being added, which directly helps young people most at risk of violence and victimization. The other is that the jobs were added consistently. Which means predictably.

Which means local governments could plan strategically. Together, all of this suggests that forecasting crime declines should take close account of employment levels in local government.

What was the Trend in Crime Before the Pandemic?

As I discuss in much greater detail at the end of the essay, forecasting crime requires three key elements. The first of those is to understand the trend before the baseline. To put it another way, if you want to predict where you are going, you first have to understand how you got to where you are.

I see a lot of analysis focused on the within-pandemic period. This makes two mistakes. First, the pandemic was clearly anomalous in all kinds of ways so focusing on that anomaly is unlikely to yield much insight. Looking at the 2020-2024 period in isolation engages in a bit of end-of-history bias, the idea that this moment is unique (and special) and different from all others. And second, it ignores the idea that crime historically moved in waves over long trends—ignoring those long-term trends is equivalent to looking at the weather without considering the climate.

As in all scene-setting, it is helpful to widen the aperture. As usual, I use homicide as a proxy for all crime. Homicide numbers tend to be valid (they measure what they say purport to measure) and reliable (they are measured the same way everywhere). And they are difficult to fudge.

The very long-term trends in crime are well known. A decades-long spike in violence in the ‘60s and ‘70s, almost two decades near the peak of violence, and then a long decline in the 1990s. The period after is relatively stable by comparison. And not very well studied. I can think of few scholarly articles that even broach the subject of crime trends in the 00s and 10s.

Shorting the timeline a little to get a more precise sense of crime trends entering the pandemic, here is what the entirety of the 21st century (so far) looks like.

The trends for the first two decades of the 21st century are a little more subtle. The century begins with an extended period of stability after the great crime decline of the 1990s, several years of a slow decline, and a reversal, before the chaos of the COVID period.

Next, let’s zoom in on the 2010s.

Trends in the last decade are also subtle but suggest that the two halves of the decade were distinct. Between 2010 and 2019, all five of the highest violence years are in the second half of the decade, 2015-2019. In other words, crime had begun to creep up throughout the end of the decade.

As is discussed later, in my opinion, this slow creep upward is easy to overinterpret. Partly this is due to the proximity of this period to the pandemic (and thus, this is a period that should provide valuable information in a post-pandemic crime forecast). And partly this is because there were huge inflections in many other aspects of American life in this period, and it is reasonable to suspect that crime trends were also affected.

Many (many) commentators have pointed to 2013-2014 as pivotal years in American society. This was the post-mortgage-backed securities crash period where the economy essentially emerged from recession into a period of stagnation. Noah Smith covers this with exceptional clarity in his essay “Why did the world break in the early 2010s?”. Here, I would like to highlight just two of his points.

The first is to highlight the employment-to-population ratio for 25–54-year-olds. This is usually referred to as the ‘prime working age population’ and this ratio is a solid indicator of the depth and breadth of economic conditions.

Following the 2008-2009 recession, only three in four prime working-age adults had jobs. In the graphic above, I include data back to 1995, which was the all-time peak in prime-age employment, for context (note that before the 1990s the percentage of prime working-age Americans who were employed was far lower, mainly because women were discouraged from working).

The big dip in the 2008-2010 period in prime-age employment is easily seen in the graphic. This fact spawned an infinity of ‘no one wants to work anymore’ memes that seem to reflect a sticky idea. But it is not true. Employment-to-population ratios have recently returned to near-record levels. This suggests that although economic conditions improved after the 2008-2009 recession, economic conditions were still sickly. This extended period of scarce jobs (coupled with a morbid housing market for those in the bottom and middle economically) appears to have had profound influences. Just to hammer this point home, Noah’s graphic shows how inequitable the recovery was across income levels—and how slow. Again, all of this economic damage occurred in the early 2010s, peaking in 2013-2014.

Finally, let me return just one more time to the local government employment chart to show this malaise in another way.

Just to sum all of this up, the trend going into the pandemic was a mild increase in crime rates coupled with a very slowly improving economic picture.

Creating a Valid Forecast

Just to bring out the bear up front, as I hope to convince you below, I find that this data together yields positive expectations about the future of crime trends in America. As I mentioned, there is a lot of skepticism about this violence decline. Partly they argue that there is not yet enough data to make a claim either way (hopefully that is settled). The other argument is that the crime and violence decline of the last 18 months is not interesting because it merely reflects a regression to the mean. This is a perfectly fine point, and there is likely some truth there—any macro trend in a nation as large as the US is likely to move toward a long-term trend after a disruption. The key question though is, what is the long-term trend? What is the mean we are regressing to? That requires a forecast.

As a rule, we forecast very poorly. And I use the vague ‘we’ here intentionally because the human condition is that we are bad at predicting the future along most dimensions. For the most part, we abandon science and rely on intuition for forecasts, where intuition is what you think about a thing before you have thought about it. Now if you have thought about a thing quite a lot in the past, your intuition is likely to be pretty good. If you have never thought about a thing before, your intuition is likely to be quite poor.

A valid and reliable forecast requires three elements. First, you must have a causal model that explains the mechanisms for the current condition. That is, you must have a clear understanding of the factors that led to the starting point for your forecast. Second, you must understand how much influence those causal forces will exert going forward—are the forces that got you where you are likely to continue, grow in influence, or are they attenuating? Finally, you much be able to say something about what new forces are likely to emerge and how they will influence the period of your forecast.

That’s all pretty daunting. Weather models do exactly this, but they have the benefit of being in a closed system. Weather is a deterministic system meaning that all the possible forces influencing future weather are known when the forecast model is run. Our social ecology is subject to all kids of factors, many of which are unknown before they emerge. That’s pretty daunting.

Still, let’s give it a shot.

For simplicity, I am only going to assume that there are two forces at play in predicting future crime in the US: COVID-related factors and long-term trends. And I am going to assume that here at the start of the forecast, August 2024, the COVID forces are small and diminishing. That’s just an opinion, it’s hard to measure empirically. So that only leaves long-term trends to explain.

Notably, COVID-19 was only one force affecting crime in the early 2020s. The other forces are shown in the Noah Smith graph above and my figures using local government employment as a proxy for bottom- and middle-income economic and social health. Here is where my thinking seems to diverge from others.

I have seen some criminologists express some reluctance to fully buy into the crime decline story because of what I imagine to be their intuition about long-term trends. I think there is a broad consensus that the trend in crime and violence was up before the COVID-19 spike. I have seen some point out that violence was up in the first two months of 2020, suggesting that trend was continuing.

If that is the prior belief, then all else being equal, this supports a forecast of a slow upward climb in the early 2020s. So, if that trend was overlayed on homicide, beginning in March 2020, you would expect that after the COVID factors have waned, the long-term trend should leave crime and violence relatively higher—not lower—than before COVID.

I want to point out that the graphic above shows a very different story from the one I hear all the time, that post-COVID crime will just regress to the mean and return to 2019 levels. But there is a flaw in this argument. Crime and violence simply returning to 2019 levels should not be the baseline forecast. Crime in 2019 did not just happen, there was an ongoing trend at work. Forecasting that crime and violence will ‘return to 2019’ levels is a prediction that the underlying trend has changed. If the pre-COVID-19 pattern had continued, crime would not have returned to 2019 levels. It would have been much higher.

But neither forecast happened.

We emerged from the COVID-19 pandemic in a completely different macro environment than the environment at the start of the pandemic. Employment-to-population ratios are near all-time highs, and stabilizing forces, like middle-class local government jobs, are near or above all-time highs. This is a much better macroeconomic environment here at the end of the pandemic than the macroeconomic environment at the beginning.

And, there have been substantial additional investments in fighting crime and violence that did not exist before the pandemic. State and local governments received hundreds of billions in federal investments. Some of that, in the tens of billions, went directly to fighting crime. But more of it went to other government functions, many of which indirectly prevent crime, violence, and victimization by removing risk factors and strengthening protective factors. And, there was a substantial investment in community violence interventions. We don’t know yet what the impact of these investments is in terms of bending the violence curve, but we do know those investments happened. Quantity has a quality all its own.

Thus, it seems most prudent to assume that the curve going into the pandemic is no longer predictive. It also seems prudent to assert that there is a discontinuity in the trend, that there is a new intercept and slope. More plainly, if we want to predict crime and violence starting from August 2024, we should begin by asserting there is a new starting point for our models and that the factors affecting the trend from here forward are much different than the pre-COVID-19 factors.

I sum, it seems reasonable to predict that when crime and violence trends stabilize, as they surely will, it will be at a level below January 2020. And we should assert that funding local government and funding anti-crime investments does affect the amount of crime and violence in the United States. Where the trend goes from there is not completely exogenous—it is not a force majeure—it is at least partially under our control.

Musical Interlude

Life is beautiful, shout it to the blue, summer sky.

Note also that there have been post-pandemic falls in crime in other countries too. Crime was on a declining trend before the pandemic, dropped further during the pandemic, but has not bounced up after. As you show, the downward trend has continued.

However, other countries have not had the additional funding that you suggest is a factor in the crime decline. The UK in particular has undergone significant public budget cuts, both in police and other public services. This would suggest that broader, transnational trends are at play. Similar societies across the globe are seeing similar crime trends, regardless of local policies and funding decisions.