Violence is plummeting in the United States. All available data from 2023 show a decline in homicide that is so large that it is near the top of all-time, one-year crime declines.

Now, crime data from the first quarter of 2024 are becoming available, and they show a homicide decline almost twice as large as in 2023.

The violence decline appears to be accelerating.

Homicide is not a particularly volatile measure, typically moving in long-slow arcs over many years. So, the rollercoaster of a historical spike in homicide in 2020 and a historical decline in 2023-2024 is without precedent.

But, rollercoasters aside, this is great news!

And we, the collective American electorate, don’t believe it. I want to talk about why we don’t believe it, why we should believe it, and what I think the cause is. And a little bit about why it matters—why it really matters, and not just for politics.

Waiting for Dumbledore

The number one reason we don’t believe there has been a massive decline in violence is that we haven’t been told that it happened by a trusted authority. We are waiting to gather in the Great Hall to learn how many points Gryffindor has been awarded for violence reduction before we consider the outcome to be decided.

This is a mistake. Because the US has no national syndromic surveillance system to monitor crime, violence, and victimization, and because the system we do have for collecting and disseminating national crime statistics is fractured, no trusted authority is going to be spreading this news any time soon.

The Violence Decline 2005-2024

But that does not make the homicide decline any less real. Here are twenty years of homicide rates in the US from 2005 through Q1 2024.

Source: Authors calculations: FBI Uniform Crime Statistics, AH Datalytics, Major Cities Chiefs Association, Council on Criminal Justice, Brennan Center for Justice.

What We Know From the FBI

The national authority on crime statistics, the FBI, has limited data beyond 2022. I used the official FBI data source, the FBI Crime Data Explorer (CDE) for 2005-2022 in the graph above.

Last month (March 18), the FBI released quarterly data for 2023. It may be possible to figure out how much violence declined in 2023 from the CDE, but if so, those answers are well hidden! Feel free to read the footnote for a longer discursion on my adventures trying to find total crime decline numbers in the FBI quarterly update.1

What We Know From Other Sources

Fortunately, there are other data. Here are my sources for 2023 homicide data.

In December 2023, the Council on Criminal Justice Crime Trends Working Group, released a report, Trends in Homicide: What You Need to Know which reported on crime trends through June 2023 and found a 10% decline in homicide. That finding was reaffirmed in a report released in January 2024 (Crime Trends in U.S. Cities: Year-End 2023 Update), which also found a 10% reduction in homicide. The report also included a sentence that I interpret as suggesting that the homicide decline was accelerating, “homicides decreased by 9% in the first half of 2023 and by 12% in the second half of the year.”

The professional society for big city police chiefs, the Major Cities Chiefs Association, released their own year-end 2023 report, reporting a 10.4% reduction in homicide.

Jeff Asher, founder of AH Datalytics, reported in December 2023, that homicide through December 7, 2023, was down 12.7%.

Each source used a different sample of cities, and there’s no clean way to summarize them, so let’s just call it a 10.5% drop in homicide in 2023.2

How about 2024?

As it happens, just yesterday (May 3rd), the Major Chiefs released their Q1 2024 crime report. And it shows a 17.3% decline in homicide.

This supports an April report that Jeff Asher released entitled It's Early, But Murder Is Falling Even Faster So Far In 2024. Asher reports the data using three samples, which show between a 20.2% homicide decline and a 20.8% decline.

Again, I lean toward the Asher estimate because he includes a validation table for his Q1 estimates and so I have a bit of a confidence interval to work with (it is +/- 6%).

So let’s call it a 20% reduction in homicide in 2024 and acknowledge it could be a little lower, or even higher nationally.

And that’s how I arrive at the chart above, which shows homicide through Q1 2024. Calculated this way, the US homicide rate is 4.5 per 100K which is well below the homicide rate at the start of the pandemic (5.1 per 100K) and only slightly above the 20 year low in 2014 (4.4 per 100K). That’s also about 33% below the pandemic peak.

Why is Homicide Falling?

Here, I’d like to return to my friend Phil Collins and pull out all the nails in this tortured metaphor.

As I argued last month, perhaps the most effective crime-fighting mechanism available to our society is an idea that exists only in a dream-like state, foggy in the half-light of wakefulness, disappearing when we reach for it. I’m talking of course about local government. Like Phil Collins, people support their local government, but you rarely hear someone say it is AMAZING. It exists in the background in a way that is always present, but rarely seen. Local government is the invisible touch.

But here’s the thing. Deep down, you probably have very strong feelings about your local government. Sure, you rant and rave about the feds and Washington and perhaps you care deeply about TikTok espionage. But your relationship with local government is what actually moves you, literally and figuratively.

Take, for example, choosing a place to live. When you buy a home, the seller’s agent will make a big pitch about the quality of the new neighborhood. And while they won’t frame it this way, their pitch will be all about how the local government is AMAZING. The local schools are outstanding, traffic flows like a Sunday drive, crime is rare, and business is booming. And part of the reason you are moving away from your old place is because the place you are leaving has a local government that you find to be LESS than AMAZING. Taxes are too high for the services you get, the local school seems sketchy, and your neighbor was robbed at gunpoint.

Local government, we cannot live together, we cannot live apart.

In my December 2023 essay, I argued why the rapid pandemic decline in local government employees in the spring of 2020 and the steady rise in local government employees in 2023 is compelling as a causal explanation for the crime decline. I don’t want to repeat myself, but I will note that some people say that the writing in that essay is beautiful, the graphics sublime, the links—dazzling, the footnotes <chef’s kiss>.3 Read it for yourself and share it with your friend.

But the key idea is that people who work most directly with young people, including those at the highest risk of committing a crime or being violently victimized were hit hard by local government unemployment. 1,250,000 teachers and counselors, coaches and cops, social workers and therapists lost their jobs between March and May 2020. Which is exactly when violence spiked. They returned steadily in the second half of 2022 and throughout all of 2023 and it was then that the violence decline gained momentum. And now, in Q1 2024, more people are doing those hard local government jobs than before the pandemic. And the violence decline is accelerating.

What Caused the Turnaround in Local Government?

Now we get to the bit that is hardest for regular folks—and criminologists—to believe. The thing about crime going up and crime going down is that it is mainly not about the police. Sure, police can deter crime. Certainly, if you lock up enough people and damn the consequences for whole classes of people and communities, crime should go down, but the details matter a lot. But police don’t prevent crime, at least not on a grand scale, and not if you are serious about what prevention means.

That’s because deterrence is about making people afraid of being caught and punished and prevention is definitely not that. Daniel Nagin, a renowned Carnegie Mellon scholar defines deterrence this way, “police deter crime by reducing offender perceptions of the probability that the crime can be completed successfully.” Further, he says, and this critical part, “in their role as apprehension agents, police are responding to a criminal event that has already occurred and by definition has not been deterred.”

So both bits matter. Despite a couple of decades of prodding to focus on problem-oriented policing and community policing, that is, to do more prevention, most policing is about apprehending suspects after a crime is not deterred and is committed.

Not to put too fine a point on it, but again, deterrence is not prevention. Professor Denni Fishbein, founder of the National Prevention Science Coalition defines prevention as the removal of risk factors and the expansion of protective factors. Further, she says, the role of prevention science is to, “identify malleable risk and protective factors [and] … assess the effectiveness of programs, interventions, and policies that target those factors.”

There are just a huge number of protective factors and virtually none of them fall into a policing rubric. For instance, protective factors include, “higher levels of opportunities for prosocial involvement in the community, recognition for prosocial involvement in school, interaction with prosocial peers, and social skills [development].” Policing does none of these things, nor is it supposed to.

And conventional policing does little about risk factors as well. The CDC lists 31 “risk factors for perpetration” of crime here. You could make the case that policing affects maybe five of the 31. Policing’s role in reducing risk factors is so small because “risk factors for perpetration” are not just about individuals, but also about their families, their friends, and the place where people live. The latter, community risk factors, include diminished economic opportunities, high concentrations of poor residents, high levels of transiency, high levels of family disruption, low levels of community participation, and socially disorganized neighborhoods. Even the most ardent law and order proponent would not argue that policing addresses those risks.

But local government does! Addressing those risk factors is a core component of local government. Local government includes an army of teachers and social workers working with individuals, families, and social networks. It also includes planners and city/county/township managers dedicated to expanding economic and community well-being.

And the reach of local government is unmatched, Walmart is the largest private employer in the US with 2.3 million employees—there are almost 15 million employees of local government. And when more than one million lose their jobs—as happened in the 90 days in the early spring of 2020—that has cascading consequences for risk and protective factors.

So that is all about why local government matters—so how did local governments’ fortunes turn around? The federal government stepped in and rescued it.

On March 11, 2021, President Biden signed the American Rescue Plan which pumped $1.9 trillion into the economy. Within that staggering figure, the $15 billion that was earmarked for violence prevention gets a lot of attention as a plausible causal mechanism for the violence decline. And that’s reasonable.

But I want to argue here that the $1.5 trillion that worked its way—one way or another—into local government was a much bigger contributor.

Just one example is the $130 billion dollars in direct funding to local governments to spur an economic recovery. Those dollars were extremely flexible, but generally focused on three pillars: government operations (including filling vacant teaching, police, and social worker jobs), public health (such as providing counseling and other prevention), and community aid (reducing community risk factors).

I am arguing here that those three pillars are all crime-fighting activities. So that $130 billion flowed directly to crime-fighting activities.

And that was just one piece of a very large pie. With all of that new investment, it should be no surprise that violence fell and continues to fall.

So Why Can’t We Accept Success?

I think there are two reasons. First, there’s always a lag between changes in fact and changes in perceptions. Attitudes and beliefs are sticky. We all rely tremendously on heuristics to navigate this complex world and it takes a while to update our priors. And, an intentional political campaign spending huge resources to convince us not to believe data and facts is slowing down our updates.

The other thing that’s going on is a very 20th-century attitude toward data. Somehow, we have been convinced that not only is it ok that official national crime statistics are not transparent, accurate, accessible, and timely. We have been convinced that it is ok that crime data releases lag by almost a year4, that the data are incomplete, that the official data tools are virtually impossible for any regular citizen to navigate without expert guidance, and that the whole system is getting worse.

But the most remarkable part of this whole story is that despite all these really big problems, we have collectively been convinced that no other source of data is valid. Mainly this is ok—national crime rates tend to move pretty slowly. But during periods of rapid change5, it is totally self-defeating.

If Phil Collins released an album and you had to wait 16 months to get it from the Federal Bureau of Music, and it came to you garbled, missing tracks, and requiring a special piece of equipment to play that you most certainly do not have, would you really not download it from another source because that source was not ‘official’?

There’s an old saying in the research community, we go to war with the data we have, not the data we wish we had.

One last tortured metaphor and I will give this up. Imagine applying that logic to health statistics. Imagine that COVID emerged in the winter of 2020 and we collectively said, well, hold on, I can’t believe that people are getting sick until I see it in the official end-of-the-year national statistics. And imagine we collectively said that it was ok to wait for a release until the entire year of 2020 had ended before any data from March of 2020 could be analyzed. And further imagine that we were ok giving the national statistical agency another nine months to clean and QC that data and release it in the fall. Altogether, that would have required us to wait until September of 2021 to believe that there was a pandemic in March, 2020 and start a response. That’s madness.

Why It Matters

Simple. To repeat another well-trod research mantra: you can’t repeat your success and you can’t avoid repeating your failures if you don’t measure them. Starting now, right now, to figure out what is going right would go a long way to sustaining those successes.

There is absolutely no way to know how long this decline will persist if left alone. In an era of climate change, it is probably inevitable that this will be a long, hot, summer and with the heat comes violence. It is not too soon to get to work.

Meet JOE!

A fantastic new resource came online this week. JOE, which is the justice outcome explorer is brought to you by a team of outstanding scholars at the University of Michigan. The Justice Outcomes Explorer (JOE), helps to “answer fundamental questions about law enforcement, criminal courts, and correctional supervision and their impact on society.” This includes prison caseloads, recidivism rates, economic outcomes during and after justice involvement, and health outcomes after criminal justice events. Check it out.

A Request for Readers

Last year I wrote 100 ways to fight crime in cities and outside of the criminal justice system. This summer I will update the list. I’ve accumulated about a dozen or so new ideas and have the same number I plan to drop, mainly based on the strength of the evidence. I’d be very interested in hearing from folks about other ideas. Thanks!

Musical Interlude

I believe in symmetry as a defining metaphysical construct. Which means, for better or worse, we must end where we started. I give you Phil Collins.

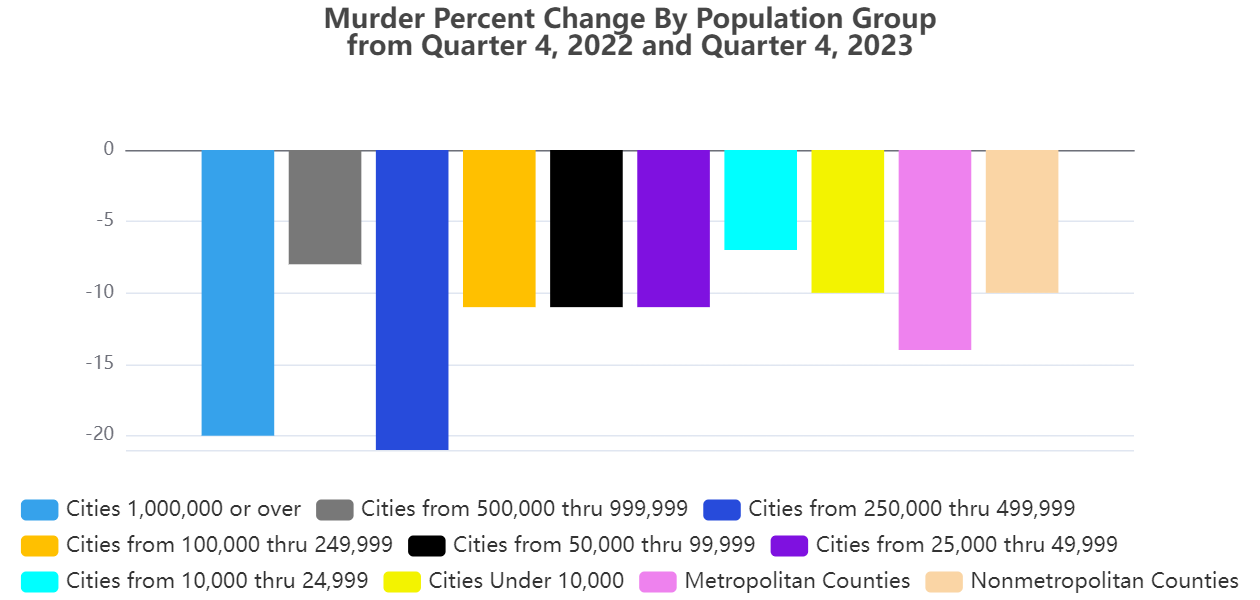

If one were to go the CDE for the 2023 data you would go to the homepage, click on ‘latest updates’, and select ‘homicide’. And you would be presented with this graphic:

I predict you could stare at those data for a long, long time and not learn the answer to the question, did murder go up or down in 2023 compared to 2022, and by how much? You might learn that homicide went down in Q4 2023 compared to Q4 2022, but how about all the other Q’s in 2023 (and in 2022)? How about a total? If there is one, it requires spelunking into unseen caves.

Quick digression. When my kid was about 9 he wanted to learn to box. So we took him and his buddy to a legit boxing coach who we reverently called, “Coach”, and my boy sniffled and sobbed a little and scuffed his feet and didn’t engage and Coach looked down at him and then up at me and said, “I can’t do anything with that.” And walked away.

In summary, as to the FBI quarterly data, let me just say, I can’t do anything with that.

I lean a little bit toward the Asher data because he has validated his sample against reported crime trends. A bit more on that can be found later in the essay.

There were no footnotes.

Here’s a remarkable paragraph from Big Local News (I have no idea what Big Local News is, but this article seems credible and the point it makes is inarguably universal). “However, because the FBI site only updates once per year, the tallies often lag public discourse. Many local law enforcement agencies publicize the statistics they send to the FBI on a much more frequent basis. For instance, as of this writing, the most recent totals in the FBI Data Explorer are for the calendar year 2020, which ended 16 months ago. Meanwhile, the Los Angeles Police Department offers a citywide snapshot each week that is rarely more than a few days old.”

The rise in the murder rate didn't have much to do with covid, it had to do with the Floyd Effect. The murder rate skyrocketed over a few days following the death of George Floyd on May 25, 2020 as The Establishment declare the Racial Reckoning. For example, the worst day in Chicago's storied history of homicide, May 31, 2020, was six days later with 18 murders.

Not sure there is super strong evidence but: Ensure schools have appropriate air filtration systems to reduce exposure to polluted air. We know pollution can cause crime and air filtration can improve student learning: https://jhr.uwpress.org/content/early/2023/02/01/jhr.0421-11642R2