The Great American Mystery Story: Why Did Crime Decline?

To stop the COVID crime wave, we must understand why crime declines: 25 explanations for the Great American Crime Decline and what it means for today

“The crime decline may be a story about ordinary people making changes to their daily lives and the resultant social stability rather than the story about cops and robbers that is prevalent in the media.”

This June, Franklin Zimring, the William G. Simon Professor of Law at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law, will receive the Stockholm Prize in Criminology. The equivalent of the Nobel Prize for criminology, Zimring is richly deserving of this honor. He has been and remains a tremendously important and influential scholar, with the gift of writing an important book with important answers before the rest of the world has come fully to grips with the importance of the underlying problem.

Indeed, in 2018 Adam Gopnik, writing in the New Yorker, credits Zimring for the phrase, The Great American Crime Decline. On that topic, Zimring’s 2011 book, The City that Became Safe offers a stinging critique of then conventional notions of why crime occurs—because some people are born criminals and stay that way—and how to police those criminals—through zero tolerance and law and order policing. Zimring offers an evidence-based counter—that NYPD was critical in achieving the massive reductions in crime and violence that took place between 1990 and 2010. Through a focus on hot places—such as open-air drug markets—and hot people—particularly gun offenders and higher-level drug dealers—crime and violence were reduced in a sustainable way.

Just six years earlier, Steve Levitt, then the Alvin H. Baum Professor of Economics, University of Chicago and now universally known as the Freakonomics guy, published a decidedly different take on the crime decline. Titled, in part, Four Factors that Explain the Decline and Six that Do Not, Levitt argues that many widely touted explanations of the crime decline were wrong. (Levitt has a delightful history of Encyclopedia Brown paper titles, including my favorite: The Case of the Critics who Missed the Point. But anyway).

In particular, Levitt argues against the idea that changes in policing strategy caused the crime decline despite it being the most frequently mentioned explanation in the media. He specifically takes aim at the idea that advances in New York City policing were responsible for the NYC crime decline stating, (pg. 172), “In my opinion, there are reasons for skepticism regarding the claim that New York City’s policing strategy is the key to its decline in crime.” Levitt argues instead that it is the more prosaic but substantial growth in the number of sworn officers—rather than any change in what they did—that explains the decline.

This specific dispute is just the alligator’s snout peeking out of the frozen swamp. Underneath the surface, there is a fierce battle across academic disciplines to find the soul of the crime decline—epidemiologists and social psychologists, communications scholars and medical doctors, social work and sociology are all in it, not to mention the economists and criminologists. Everyone has a theory and empirical evidence.

My guess is that many people reading this (if many people read this) have their own pet theory. Here’s an out-of-the-box idea that has gained significant popular support. Kevin Drum said this much better than I can:

Experts often suggest that crime resembles an epidemic. But what kind? Karl Smith, a professor of public economics and government at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, has a good rule of thumb for categorizing epidemics: If it spreads along lines of communication, he says, the cause is information. Think Bieber Fever. If it travels along major transportation routes, the cause is microbial. Think influenza. If it spreads out like a fan, the cause is an insect. Think malaria. But if it’s everywhere, all at once—as both the rise of crime in the ’60s and ’70s and the fall of crime in the ’90s seemed to be—the cause is a molecule.

The molecule being lead (Pb). The idea is not Kevin Drum’s of course, but Jessica Wolpaw Reyes’ who wrote Environmental Policy as Social Policy? The Impact of Childhood Lead Exposure on Crime where she presented evidence that “the reduction in childhood lead exposure in the late 1970s and early 1980s is responsible for significant declines in violent crime in the 1990s.” For proponents of the lead-crime theory, as it has come to be known, I would just point out that it is lead in gasoline that enters the bloodstream of children through the atmosphere rather than lead paint or lead in drinking water that is the culprit in this narrative.

But for every molecule that explains everything, there is another molecule. Steve Levitt (with Prof. John J. Donoghue) is an earlier paper pointed to another massive change in the 1970s with similar strong evidence that the change led to the massive decline in crime in the 1990s, through The Impact of Legalized Abortion on Crime.

Why it Matters

This all matters at the present moment in a way it has not over the last two decades. A declining crime rate or a steady crime rate at a relatively low level is our default narrative. It is the baseline from which we begin negotiations about how to deal equitably or forcibly with the crime that remains. If you are under age 50, you are generally safer today than you have ever been.

But that changed dramatically last year. Last month I wrote about 2020’s wave of violence and why I do not expect the wave to recede along with the pandemic.

So, what can we learn from the crime decline that is useful today? What caused the crime decline and is any of it repeatable? I think there are a lot of important clues in the literature around the Great American Crime Decline. To see them clearly though, we have to approach the literature with an open mind and apply patience and persistence in applying the lessons. Because the big lesson is that patience and persistence is the ultimate solution.

There is surprisingly little evidence that the answers to crime prevention lie within the justice system. What the evidence suggests instead is that the ‘prevention’ part of ‘crime prevention’ is most important. And much more important than the ‘crime’ or the ‘crime-fighting’ part.

But first, did Crime Actually Decline in America?

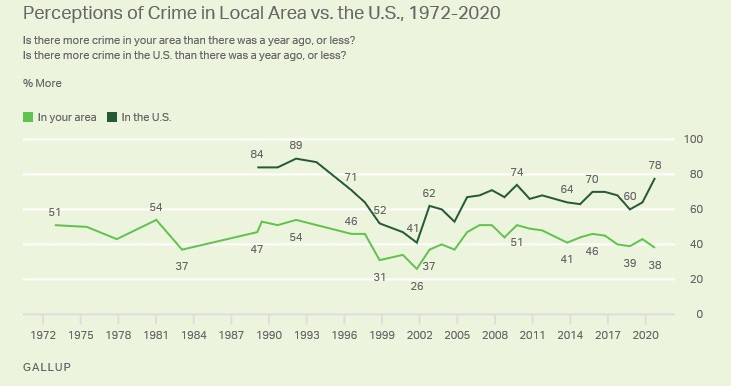

At this point, I presume you are ready to cut to the chase and hear some sort of conclusion to this mystery story. Although I have tipped my hand a little with the Vanessa Baker quote and the prevention tease, I think it is important to convince you that there WAS a crime decline. If the polling data are correct, many of you don’t believe crime declined. And this isn’t some FAKE NEWS phenomenon that flared up recently—the polling data say loads of you have never believed it.

This Gallup poll finds that in most years 60-70% of Americans think crime in the US is worse than it was the year before. As I will show you next, year-over-year property crime declined in 27 of the 30 years studied, and violent crime in 23 of 30. Crime has almost always been declining since 1990, and Americans almost always think it is getting worse.

The Great American Crime Decline

So, as Warner Wolf used to say on my local sports news, “Let’s go to the videotape!” Or in this case, “Let’s go to the Excel figures!” Or whatever. Anyway, first, I should note that you can’t just go mucking about recklessly throwing around crime figures. Crime is a latent variable in the academic sense that it cannot be directly measured, it can only be described through its components (beauty is probably the best example of a latent variable). So there are loads of ways to measure crime and the crime decline.

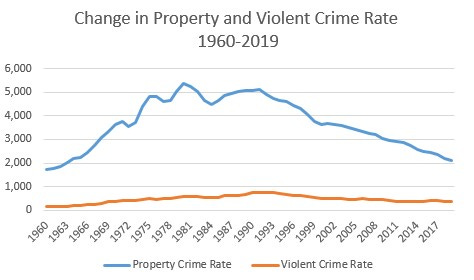

One way to measure the trajectory of crime over time is through brute force, by jointly considering all reported crimes.

We can start in 1960 when the modern FBI Uniform Crime Report data was first collected and published in the form we know it today. In the simplest terms, there was a period of steadily rising property crime (the blue line) in the 1960s and 1970s that remain exceedingly high in the 1980s and has substantially and continuously declined ever since the early 90s. But since there is so little violent crime relative to property crime, any ‘all crime’ measure is really just a measure of property crime.

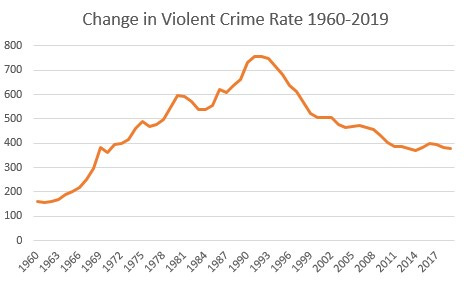

Once scaled appropriately, the violent crime story is much more compelling and reveals important differences from the property crime story. While the decline from the 1990s onward shares a trajectory with property crime, it does start quite a few years later. And, there is no plateau really in the 1980s, more of a steady increase. And while the property crime rate has twin peaks in 1980 and 1991, violent crime rates clearly summit in 1993. But there is some subjectivity in the violent crime definition—most of the category is made up of aggravated assault and robbery (robbery is defined as taking something off a person by force or threat of force). There were changes over time in reporting, due in no small part to whether victim complaints from women and people of color were counted or not. Surely, that changed over time (but not enough!!).

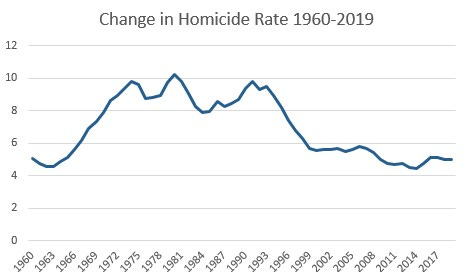

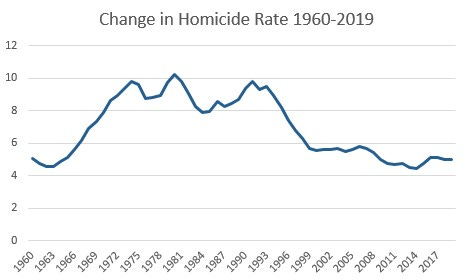

While there are all sorts of scandals about police falsifying the number of serious crimes, which should give pause to anyone using the violent crime rate, it is much harder to falsify a homicide report. Criminologists, therefore, tend to lean on homicide data in measuring ‘crime’. And the pattern in homicide rates is different again from the first two series—the peak is much earlier and more persistent, with a peak of 9.8 murders per 100,000 in 1974 and again in 1991, with an even higher peak in 1980.

It is the trend line in homicides that is most compelling. The steady decline throughout the 1990s is consistent, but the pattern is more nuanced. There is no real change from 1999 to 2005 and a little bump in 2005 and 2006 (now Prof. Aaron Chalfin and I offered a hypothesis on this one you can read here.) A long, slow decline follows until about 2015 where homicide increases a little and stays at a higher level. The FBI has not yet reported on 2020, which was a dreadful year, but my best guess is that the homicide rate will be higher than any year in the 2000s.

So, the first important point is there is heterogeneity in the outcomes we seek to explain, depending on how you measure crime. Any really convincing narrative on the crime decline should explain each of these curves, or be clear why it does not.

25 Reasons Why Crime Declined in America

So now, finally, we have arrived at the point where I can describe the most important theories about why crime declined. This list is a little bit of a labor of love in that I have been curating it for twenty years. I didn’t offer any judgments about the relative merits of the Zimring claim that changes in police practices explain the crime decline or the Levitt claim that it is the sheer number of police that matter. In fact, I think both theories have substantial merit.

And so to do all of the other items on this list. For each, I have provided a link to a paper that rigorously makes a compelling claim for the idea. In fact, having a list of 25 explanations for the crime decline was completely arbitrary—I could have added at least a dozen more (and in fact my list here is more like 35 theories since I have grouped some similar ideas and snuck in a few extra).

So, without further ado, here is the list. The first bunch of causal mechanisms for the crime decline has been explicitly linked by researchers to the crime decline and the link makes that connection. The rest of the ideas on the list are mechanisms that mediate criminal behavior. I am linking these mechanisms to the crime decline because changes in the extensive margin (how many people experience the proposed mechanism) are large and inclusive and changes and change at the same time as the crime decline. I add a sentence for the mechanisms that aren’t obvious, but each is worthy of a book-length treatment. Graduate students: all of these are testable hypotheses. Have at it.

Mass incarceration (Truth In Sentencing/Three strikes/Mandatory minimums)

More community-based organization serving at-risk neighborhoods

Decreased drug use/alcohol consumption for 16 and 17 year-olds.

Widespread use of medication (Ritalin, anti-anxiety, anti-psychotic, anti-depressant)

In-home entertainment (internet, video games, pornography, cable)

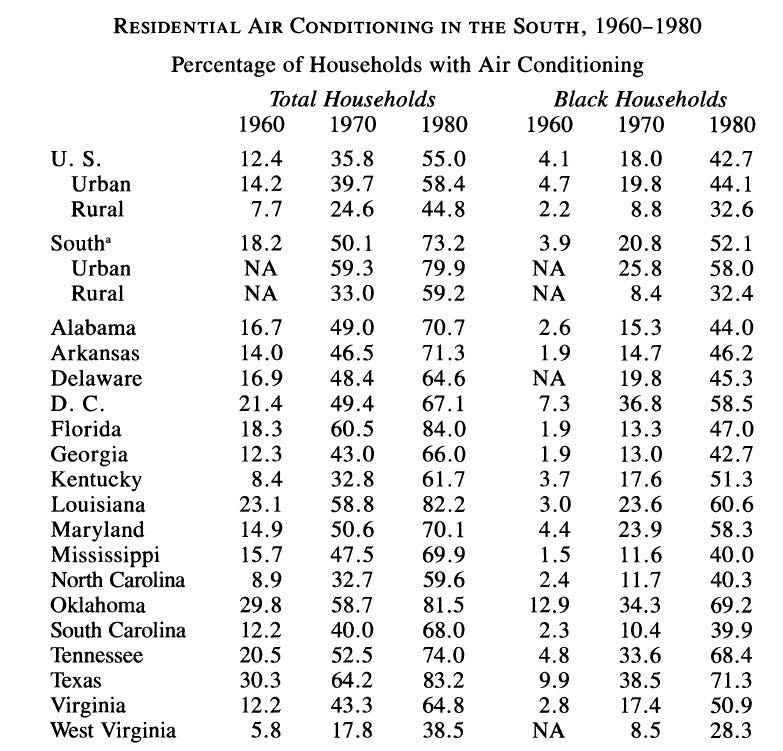

Air conditioning. The hypothesis here is that the ubiquity of air conditioning in residential buildings led to a massive change in routine activities. If you are home, you are far less at risk of most types of victimization, and your property is safer as well. Air conditioning is a far more recent phenomenon than you might imagine. Here’s a table showing that by 1980, only about half the homes in the south had air conditioning.

And some other explanations that are credible (but I think they are wrong)

Concealed carry/gun ownership. This is posed as a deterrence mechanism. At the same time, there is iatrogenic evidence that expanding protections for the use of firearms increased violence (see The Trace summary of Stand Your Ground research).

More police. The idea of police officers as an undifferentiated commodity where there is a fixed marginal benefit to an additional officer seems implausible to me. There must be diminishing marginal returns such that more is not always better.

Labor market expansion/Changes in employment. This a massive literature with so much heterogeneity in mechanisms and outcomes, it is hard to summarize. The evidence that stable employment is a critical mechanism for desistance from crime is strong, but the evidence linking macroeconomic ‘employment’ to crime trends is much less convincing.

Law and order/Proactive policing/Stop, question and frisk. Here’s an entire chapter of citations from the National Academy of Sciences on why these policies and practices are counter-productive.

This list should be accompanied by a roomful of caveats. One important caveat is that it is really hard to disaggregate policing mechanisms—it is hard to say where situational crime prevention starts and HotSpot policing or Problem-Oriented policing or Proactive policing ends. It is also hard to disaggregate punishment mechanisms, that is to say, which of Three Strikes/Mandatory Minimums/Truth in Sentencing is most responsible for mass incarceration.

All of this stuff is endogenous, meaning changes in crime may affect the mechanism. That is, if crime goes up, the economy gets worse, causing crime to go up. And, many of these explanations are simultaneously determined within an individual. If obesity leads to disability, a person’s ability to commit certain types of crime declines. But, obesity/disability also reduces their income, which increases their risk for committing a crime. And, the disability itself increases the likelihood of victimization, and victimization is a surprisingly large predictor of new criminal activity.

Final caveat. The argument here is that these factors caused the crime decline, at least in part. That does not mean the mechanism passes any sort of cost-benefit test! That doesn’t mean we should do more of it!! Mass incarceration was obviously hugely destructive to communities, particularly deeply disadvantaged communities of color. It fails the cost-benefit test. But mass incarceration is certainly a key explanation for the crime decline. If we as a society choose to incapacitate enough people, there will certainly be less crime for the fortunate few who remain free.

But, wait, why did crime go up in the first place?

Great question. Proposals explaining the end of the crime decline are rarely proceeded by a discussion about why crime first increased. The best and most convincing explanation for why any phenomena stop is that the stimulus that created it is removed. I won’t go through the same exhaustive exercise for why the crime wave started in the 1960s, but there are any number of explanations that are widely held:

The counter-culture and the end of law and order

Women entering the labor force and the end of traditional male role models

White flight from cities

Widespread drug experimentation

Lax deterrence (limited severity of punishment)

Underfunded police (too few police=low certainty of detection)

Beginning of a series of narcotics epidemics

Closing of mental health hospitals without available community supports

Deindustrialization

End of mandatory military conscription for young men

I have no doubt this list prompts eye-rolling in many quarters. It is, to be sure, partially a list of culture war stuff. But the insight here is not that this list is right but that culture matters. The draft, for instance, has two different mechanisms for reducing crime. One is that it essentially incapacitated young men for at least part of their prime crime years. The other is that it promotes the development of a sense of self-discipline which surely for many young men continued after their service. As they say in Silicon Valley, culture eats strategy.

Evaluating the Crime Decline Explanations

There have been a couple of notable efforts to synthesize this enormous crime decline literature, and surely there are more. In 2015, the Brennan Center for Justice released a fascinating report that summarizes the relative contribution of several of these factors, and you can find that report here. Another favorite of mine is the 2009 book, Crime Drop in America, with nine essays by leading experts in their area of inquiry.

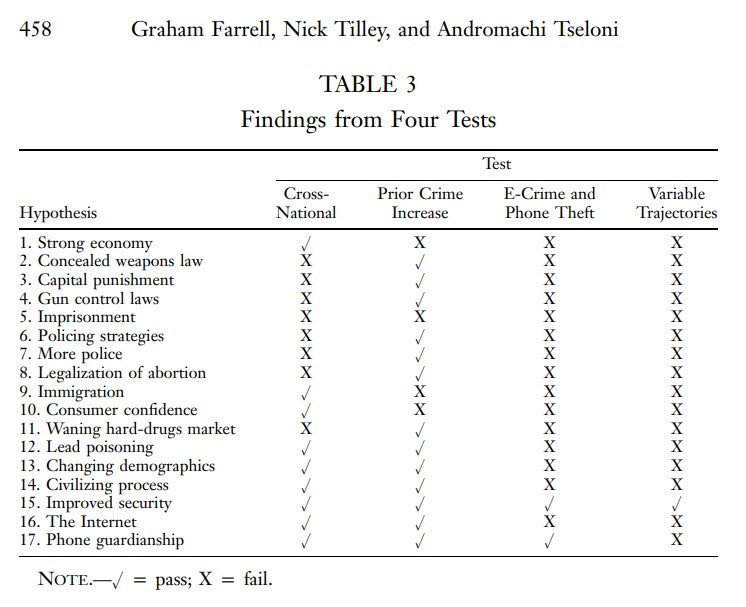

I want to spend a minute on a third synthesis, one that comes to us across the pond. University of Leeds Professor Graham Farrell has written a series of papers based on a simple, yet utterly profound insight into the crime decline. He and his colleagues argue that in order for a crime decline explanation to be convincing, it should be true for all similar countries that experienced a contemporary crime decline. If you apply that logic to the list of crime decline explanations, you get this:

The takeaways are that only some of the crime decline explanations hold up cross-nationally, only some explain why crime rose in the first place, and almost none meet both criteria.

What does hold up is that changes in individual behavior, attitudes, and beliefs matter, as do the rules that define the shared culture. The criminal justice system matters far less when it comes to seeding and nurturing crime declines.

How do we learn from the Crime Decline to Prevent a new Crime Wave?

What should be clear from all of this is that many of the most compelling explanations for the crime decline have nothing to do with the criminal justice system.

So what should be done today as we face a new crime wave? One idea that is getting too little traction at the moment is the idea of directly investing in the processes by which “ordinary people” make changes in their daily lives that create social stability.

The word for this is prevention. Prevention which reduces risks. Prevention which creates opportunity. Prevention which focuses on creating strengths. Prevention which removes structural barriers. Prevention that makes the daily journey a little less difficult, especially for those who start behind because we have forced them to start behind. Prevention that is based on building assets, not deterrence which builds fear.

Much more to say on this down the road.

Musical Interlude

This is one guy with a two-string, twelve-foot guitar, a beer bottle for a capo, and a wood drum. He built himself. I dare you to listen and not feel joy. Video does not embed but here it is. Buy the album!

FYI, my own variation on the Pb crime hypothesis:

https://we.tl/t-iBdu9iftqj

The meat is in chapter 4. Includes ongoing issues of Pb paint (including additional poisoning from clean-up measures under 1992 abatement law, and how the epidemiology is designed to miss it---section 3 of chapter 4); I hold that the cleanup resulted in a small epidemic that peaked around 2001-2ish, as the old LEAD SAFE regulations required spray bottle and hand sanding, which no financially sensible contractor would do. I recall sanders with vacuum attachments and HEPA filters for shop vacs only became popular and acceptable for abatement activity later.

Also, crimes modulated by sociological tendencies, i.e. crime requires means, motive, opportunity (unemployment means more hours of opportunity), and proclivity (principally Pb).

Finally ethnoregional variation in uptake per unit intake of Pb gives account both of e.g. higher black BLL vs white, and thus also of apparent genetic signal in IQ.

google genetics