Why Doesn't the Public Believe Crime has Declined?

Important lessons from taking the skeptics seriously

A couple of weeks ago, I had a chance to have a conversation with the great Pastor Nick Taliaferro on Evening WURDS. The topic of our talk was the Great American Crime Decline following up on a prior newsletter. While we talked about the myriad possible explanations for the crime decline, there was an underlying question that tugged, which was, do people really believe crime declined? I hear this question in the academy too--I’ve taught a dozen courses over the years that touched on the crime decline, and while my students feign adherence to the data that shows that Americans are safer than they have been since the 1960s, I don’t think they really believe it.

The purpose of this week’s newsletter is to ask the question, why doesn’t America believe there is a crime decline? And is there wisdom in America’s skepticism? Is the crime decline overstated in some way such that amour propre has been committed in the halls of justice? As we consider whether the Great American Crime Decline of 1990-2019 has transformed into the Great American Shootout of 2020, it’s worth considering whether the important lessons for this moment live not in those places where the crime decline was tangible, but rather, in those places where it was not.

The case for the Great American Crime Decline is strong. In the years around 1990, crime and violence in America hit a peak in both real and per capita numbers. By 2000, the per capita violent crime rate reported by the FBI was about one-third lower than the 1990 level. The decline in homicide was even steeper, falling nationally by almost half in just one decade. Up until last year’s pandemic fueled violence wave, violence continued a slow decline and by 2019 the violent crime rate was almost exactly half of the peak rate of violence.

And, even though the population of Americans grew by 75 million between 1990 and 2020, more than one-half of a million fewer Americans were violently victimized each year in the 2010s.

“The decline in crime has also been remarkable in its steady persistence. Homicide rates fell in nine of the ten years in the decade of the 1990s, with the only exception being a minor upward blip in 1992. In the previous three decades, homicide had never fallen for more than three consecutive years. Robbery, burglary, and larceny each fell every year between 1991 and 2000. Prior to 1991, robbery rates had fallen in only eight of the preceding 30 years.” Levitt, 2004

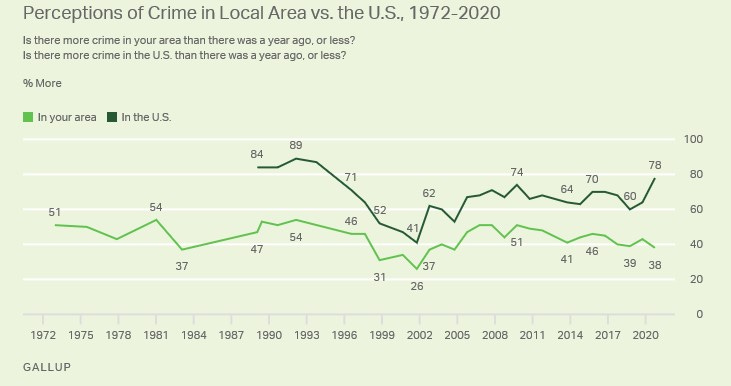

But Americans don’t believe it. When you ask Americans if their neighborhood is getting safer, they say it is. When you ask them if their city or the country as a whole is getting safer, they say it is not. While crime is no longer at the top of most Americans’ list of policy priorities that seems only to reflect a belief that the fire no longer rages.

Now, among the literati, it is de rigueur to take this as evidence of an uninformed electorate. It is evidence that slack-jawed rubes in ersatz suburbia have been force-fed local media hysteria where if it bleeds it leads. Or, it is at least evidence that the voices of those in the academy who know best have not been given their proper due. I’ve certainly made some of these arguments, though more politely.

But let’s suppose instead that the public opinion data is showing that the people are witnesses to something that is not reflected in the national averages. Let’s suspend our informed disbelief for just a second and see what’s really going on in town. What’s the view from their window?

What the Academy Believes

There is really no debate in academia about whether there was a crime decline. And I’m not debating it either. What I am questioning is whether a crime decline is both a necessary and sufficient precondition for people to feel safer. I am questioning whether it is sufficient.

There is no definitive article on the crime decline in the same way the law and order doctrine is defined in Kelling and Wilson’s Broken Windows article. But let me work through an article that I think captures the spirit of the crime decline genre.

A regular reader of this newsletter will recognize that I am a fan of the work of Steve Levitt who was perhaps the first public economist to apply rigorous econometric tools and reasoning to the applied study of crime and violence. In 2004, Levitt published Understanding Why Crime Fell in the 1990s: Four Factors that Explain the Decline and Six that Do Not a paper that reflects on the decline in crime from 1990-ish to 2000. One of the reasons I am a fan of Levitt’s work is that he does not skip the steps in his thinking that many of us gloss over. In this article, that means that before plowing into the reasons for the crime decline, Levitt first seeks to establish that there was a crime decline.

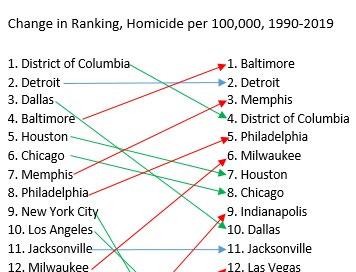

Levitt presents the table below to statistically describe the violence experiences of 25 large American cities to establish prima facie evidence of a decline. The idea is to compare peak homicides to homicides ten years after the crime decline.

Levitt notes that crime declined for every city on the list above and cites that fact, the sheer size of the decline, and the finding of at least some decline in crime across geographies (urban/suburban and rural) and city-level demographics as evidence of a decline that was national in scope. He concludes with this statement, “[t]he universality of these gains argues against idiosyncratic local factors as the primary source of the reduction.” While Levitt has established a correlation, I would argue that his statement is really a hypothesis worthy of testing rather than a causal inference supported by an empirical test of that hypothesis. I think there is much to examine here, and, that much of the disconnect between public perceptions and the academic community is around the tremendous amount of work that the word “universality” is doing in that sentence.

There are at least three bits to this analysis that give me pause[1].

First, I would point out it is a bit disingenuous to use the ‘peak’ of violence as the baseline to discover a trend. A local maxima or a global maxima is just that, the highest point around. By definition, everything around it must be lower. Concluding that violence is lower than its peak is a tautology, not evidence.

City-level data from that period is hard to find, but if you took an average of the years listed as peak years here—1985-1994, instead of just looking at the peak year alone, you would come to a different conclusion about the crime decline. You would find, for instance, that homicide in Baltimore and Milwaukee did not decline at all. In Baltimore, homicides per 100,000 residents between 1985 and 1994 averaged 37.4 per 100,000 and 38.7 in 2001. In Milwaukee, the 1985-1994 homicide rate was 19.1 before climbing more than 10% to 21.1 in 2001. There are other examples, but you get the idea.

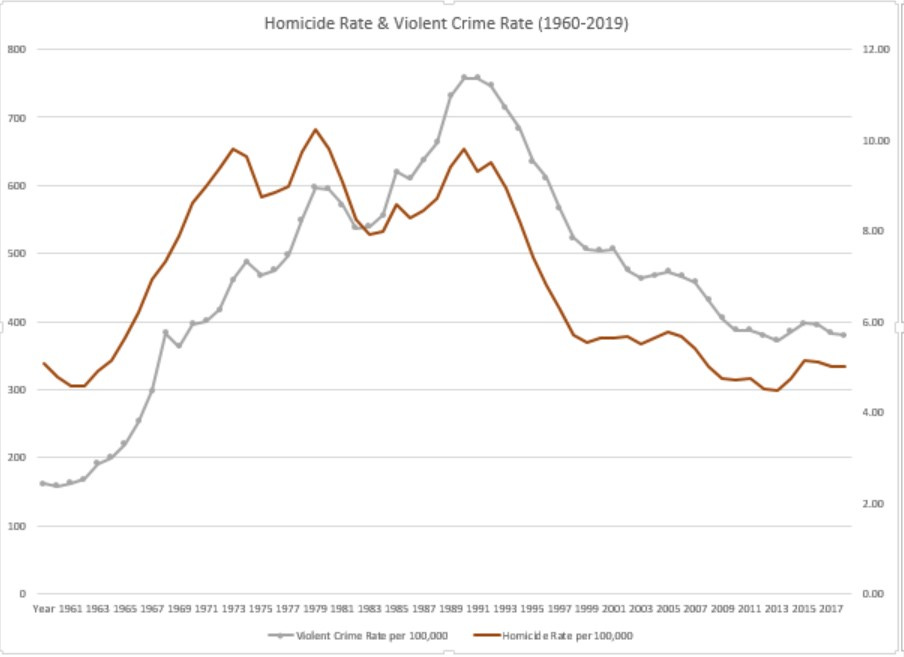

Second, violence is always difficult to measure, and many criminologists (including me) often use homicide as a shorthand for overall trends. After all, monkeying with crime data is a despicable but time-honored tradition and homicides are hard to fake in the data. But the idea that violence and homicide numbers are always correlated is much more of a testable hypothesis than a fact. Consider the graphic below, wherein the red line is homicide and the gray is violent crime.

The key idea from the graphic is that while correlated, violence rates and homicide rates are not perfect substitutes, they do not measure the exact same thing, and homicide is only an approximation for violence. In the graphic, the peaks of homicide and violence do not coincide. The increase in violence in the 1960s and 1970s was much steeper for violence than for homicide. At the end of the series, violence levels in 2019 resemble violence in the early 1970s while homicide rates resemble rates from the early 1960s. Anyone with a clear grasp of American history will note that 1961 and 1971 were very different eras in America with respect to crime and safety.

The last point, the main point, the pressure of social structures

The last point is really about the relative safety and this is what I really want to talk about. There is a school of thought in criminology called anomie theory that Robert Merton (1938) describes as repudiating biological theories of crime and instead focusing on, “discovering how some social structures exert a definite pressure upon persons in society to engage in conformist rather than nonconformist behavior.”

Modern strain theory builds on this idea that social structures affect deviance by asserting that relationships, and relative position, matters:

Strain theory focuses explicitly on negative relationships with others: relationships in which the individual is not treated as he or she wants to be treated. Strain theory has typically focused on relationships in which others prevent the individual from achieving positively valued goals.

Simplifying the framework, I would argue that it is the idea that it is not someone’s absolute status in society that determines their attitudes and beliefs, that tempers or accelerates their hopes and dreams, but rather their relative standing dictated by social structures. By that measure, what matters is how well you are doing compared with others you know and others you know about. And, how well your community is doing relative to other places.

The idea here is simply to note that if some places are doing well in reducing crime and other places are doing relatively poorly, then that gap becomes a source of strain. This holds even if the Levitt data are correct that every city experienced a crime decline (which they did not). In the presence of very divergent experiences with the crime decline, it becomes something a vicious cycle where the gap creates strain, and a persistent gap exacerbates the strain.

Heterogeneity in the Crime Decline

It is hardly noteworthy to make the point that there was heterogeneity (variation) in how much a crime decline individual cities experienced. In every distribution of any data, some places fall above the mean, and others below. What matters is the shape of the distribution. We tend to imagine every distribution as a bell curve, with most observations, in this case, the crime decline in the top 25 cities, being around the mean. Maybe a little above, or a little below, but close, with maybe an outlier or two.

That is not the story of the crime decline. Between 1990 and 2019, homicides in New York City fell by almost 90%, from 2,248 in 1990 to 318 in 2019. In Baltimore, the peak homicide was 355 in 1993, and in 2019, there were 348 murders. But the population fell by more than 140,000 in between and as a result, the homicide rate rose 22%. NYC and Baltimore are not merely outliers on the crime decline distribution, they experienced two completely different events.

Let me return briefly to the Levitt paper. One sort of obvious refinement to the simple presentation of the percentage of crime decline from the peak is to rank-order the cities from most dangerous to least dangerous and observe whether cities change their relative ranking. If the cities simply reduce their crime rates and retain their ranking that tells a story about heterogeneity. If the rank-ordering changes, that is evidence of the additional problem of strain.

Clearly, there was a lot of movement among cities in their level of violence relative to other places. There are a number of success stories. Dallas moved from the 3rd highest homicide rate in 1990 to the 10th in 2019. Los Angeles fell from 10th to 17th. Boston declined from 13th to 18th.

But the big story is, of course, the New York City miracle. In 1990, NYC was ranked as the 9th most violent big city in America, but by 2019, it was ranked 21st (out of 25). That is an astonishing change in fortunes and has led to innumerable books and articles on the causes and consequences of the miracle, among the best of which is Franklin Zimring’s The City that Became Safe.

The question is not whether NYC was an outlier, it certainly was, but rather, how many other cities experienced the crime decline in a way that makes the claim of “universality” dubious.

The insight here is that few cities on this list have reason to celebrate, despite the overall giant decline in crime. Eleven cities moved up the ranking of violent places, including big jumps for Las Vegas and Indianapolis. Milwaukee, Philadelphia, and Memphis all moved closer to the top of the list, where Baltimore and Detroit remained. Even among cities that moved down in the rankings, three (the District of Columbia, Houston, and Chicago) remain in the top third of most violent big cities.

There are winners on this list as well. A lot has been written about winner-take-all urbanism and the rise of superstar cities. Here, it is quite clear that those superstars—NYC and Los Angeles above all others, but Dallas and Boston too, have experienced a different crime decline than almost everybody else. Strain theory is not magic, it just acknowledges that we are all aware of who is winning and losing and we measure our own success against the winners. And we all know whether we live in a superstar city.

My guess is that those rankings, and the movement within those rankings, have a substantial effect on Americans’ perceptions of the Great American Crime Decline.

In summation

So which is the real story of the crime decline? Is it a victory over a really hard social problem or a lingering dystopia? The point here is that it was both. The number of non-superstar places that experienced something other than unbridled success far outweighs the number of places that experienced notable gains.

And it is something of a vindication of the public, and my students, who have maintained a skeptical attitude throughout.

[1] A small point, but the list itself is a curious one. Cleveland, Nashville, and New Orleans were among the top 25 biggest cities in 1990, but are not on the list. But Denver, Austin, and Honolulu (44th biggest city) are. Austin grew into the top 25, rising to 16th most populous by 2000, but Nashville was 22nd on both the 1990 and 2001 lists but not included.

Really helpful article John. While outside of the subject matter, it is important to note that perceptions of crime are shaped, in part, by the media and politicians (maybe more of question?). Many of the regressive and racists policies that created mass incarceration were initiated in the late 1960s -1970s. Even as crime has declined we have struggled to make significant headway in reversing these policies.